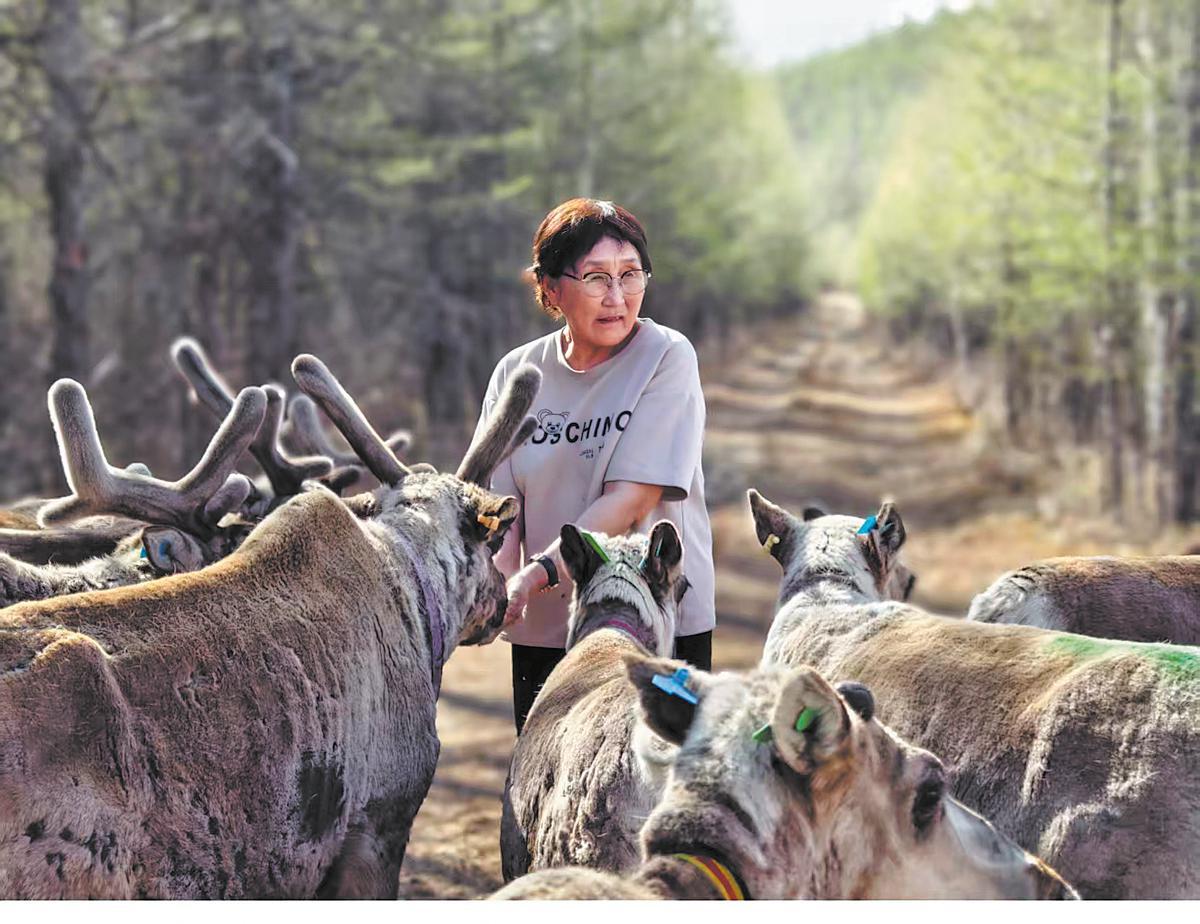

Dekesha Kaertakun tends to reindeer in Olguya town of Genhe, Inner Mongolia autonomous region. Yiqie Kaertakun/For China Daily

Editor's note: As protection of the planet's flora, fauna and resources becomes increasingly important, China Daily is publishing a series of stories to illustrate the country's commitment to safeguarding the natural world.

Deep in the primordial forests of North China's Inner Mongolia autonomous region, the gentle chime of reindeer bells is the sound that defines a way of life.

For the around 300 Ewenki people who inhabit the Olguya Ewenki ethnic township of Genhe city, their bond with reindeer is one of the most specialized human-animal relationships in the world. Unlike larger nomadic groups in the Arctic who primarily raise reindeer for meat, the Ewenki use reindeer to transport household goods, for riding, for their milk, and as spiritual companions. Reindeer are deeply embedded in their culture.

For decades, this unique bond faced the threat of extinction as the lure of the city pulled the younger generation away. But today, the tide is turning. As 67-year-old elder Dekesha Kaertakun observes, the mountains are calling their children home.

"Between 2008 and 2015, my heart was heavy," said Dekesha. "I used to tell my peers that as long as there are reindeer in the mountains, there will be Ewenki to raise them. I had to believe that to stay hopeful."

Youta Kaertakun feeds reindeer at Olguya town in Genhe, Inner Mongolia autonomous region. CHINA DAILY

For about two decades, the population of reindeer in Olguya has remained at around 1,000, Dekesha said.

But the demographic of the herders is shifting. "I feel much more optimistic because the younger generation is eager to go up the mountains. They've developed a genuine love for animal husbandry and the enjoyment of nature. This is a big step forward. I'm proud that the Ewenki have successors in reindeer herding," she said.

Among those returning is a young Ewenki named Youta Kaertakun, Dekesha's niece.

"The main reason I raise reindeer now stems from my upbringing. Growing up in this environment with my elders instilled in me a sense of duty to pass down these experiences and traditions to future generations," the 37-year-old said.

After graduating with a major in Chinese language and literature from Hulunbuir University in 2012, she went to Mohe city in Heilongjiang province to find a job in tourism.

"Back then, there were few job prospects in my hometown. Raising reindeer wasn't profitable due to the costs of vaccines and winter feed. Traditionally, moving reindeer required a lot of crew, but now we use vehicles, which adds to the expenses," Youta said.

Dekesha Kaertakun tends to reindeer in Olguya town of Genhe, Inner Mongolia autonomous region. YIQIE KAERTAKUN/FOR CHINA DAILY

The Ewenki's way of life had already undergone a seismic shift in 2003, when they gave up hunting to become the permanent guardians of the environment. While the government provided modern housing, healthcare and schools in Olguya town, the reindeer remained in the highlands. People were able to choose whether to live in the mountains or in the lowlands.

In 2016, Youta chose the peaks. "My parents were aging, and after getting married and pregnant, I wanted to focus on family. Another important reason was that I had realized the unique value of my culture," she said. Her employer in Mohe was deeply interested in her Ewenki roots, making her realize that her "ordinary" upbringing was actually a cultural treasure.

"I was born and raised in the mountains, living there until it was time to start school. During school vacations, I would return to the mountains with the elders. That's how I grew up," she said.

In 2016, she began working with her father raising reindeer and focused on learning and preserving the local culture.

Boots of Ewenki style are on display at the museum. WANG YONGJIE/FOR CHINA DAILY

Tourism has become a significant source of income for some Ewenki, said Dekesha. "Taking 20 reindeer to a major local tourist destination can generate about 60,000 yuan ($8,600) in two months during the peak season. The reindeer serve as attractions, assist in transporting goods, and offer photo opportunities for visitors," she said.

Youta added that locations are selected that offer better natural environments for the reindeer."This is our livelihood, and we can't change that. We need to keep living and earning money to sustain and nurture such a large herd," she said.

A turning point for the community came in early 2024 during a trip to Harbin. Youta and her peers brought eight reindeer to the city's historic Central Street as part of a cultural showcase. Overnight, they became an internet sensation.

"My Douyin followers jumped from nearly 1,000 to over 10,000 in three days," Youta said. Surrounded by flashing cameras and curious crowds, she and her young peers felt a rush of excitement.

"We were like celebrities in our traditional clothes. Everyone wanted photos, asked where we were from."

Dekesha Kaertakun tends to reindeer in Olguya town of Genhe, Inner Mongolia autonomous region. YIQIE KAERTAKUN/FOR CHINA DAILY

But that evening, amid the thrill of viral fame, her aunt Dekesha asked a question that cut through the noise: "When you were walking on that busy street, could you still hear their bells?"

The room went silent. In the roar of the city, the soft bronze chimes — the very sounds that allow a herder to locate a deer a kilometer away while lying inside a cuoluozi (a traditional birchbark tent) — had been drowned out.

"The city was too loud for the reindeer," Youta realized. "They were overstimulated, and their health was at risk."

The next morning, the group packed up. There was no debate. Fame was temporary; the well-being of the "family" was paramount.

Dekesha examines an exhibit representing the Ewenki hunting lifestyle at a museum in Olguya. YIQIE KAERTAKUN/FOR CHINA DAILY

Raising reindeer remains a grueling physical task. Reindeer are nocturnal, roaming freely at night to feed on lichen, wild mushrooms and matsutake. During the day, they are lured back to camp with salt and soybean cakes — not for hunger, but as a "social" reminder of their bond with humans.

If a deer wanders off, the search is a test of endurance. "If I walk for more than four hours in deep snow, my legs feel like lead," Dekesha said.

In her spare time she teaches younger generations herding skills, traditional Ewenki songs, stories and language. With the help of modern technology, such as smartphones and the internet, she can now teach these online.

A baby cradle of Ewenki style is on display at the museum. WANG YONGJIE/FOR CHINA DAILY

Xie Fengyan, a retired associate professor at Genhe's Party school who specializes in Ewenki history, said that reindeer are integral to the Ewenki's way of life. Historically, the Ewenki in Olguya domesticated the animal for transport. Over time, reindeer became essential and the Ewenki regarded them as family members, passing this bond down through generations.

"However, if the younger generation doesn't maintain this connection, the culture risks fading. The animal's population faces challenges like inbreeding among reindeer, which affects their quality. In addition, wild animals like lynxes, bears and wolves often attack reindeer herds," she said.

"Unlike cities like Beijing, where technology and resources abound, they often lack basic amenities like electricity and phone signals in the mountains," she added.

Snowboards of Ewenki style are on display at the museum. WANG YONGJIE/FOR CHINA DAILY

"Despite these challenges, many young Ewenki are returning to the mountains to preserve the reindeer culture. This is a positive sign for the Ewenki. It's commendable that young people choose to leave behind modern comforts to embrace mountain life, reflecting a deep-rooted commitment," Xie said.

Youta remains steadfast. She documents her life on the mountain, posting videos whenever she finds a bar of signal. "I don't want a future where Chinese people have to go abroad to see a reindeer," she said. "As long as we stay, the bells will keep ringing. Visitors can walk with us and see the reindeer, unafraid and naturally interacting with them. For us Ewenki, this is the essence of our existence."

Contact the writers at lihongyang@chinadaily.com.cn