Resident doctors hold placards in London on Wednesday — the first day of the latest five-day strike over pay and jobs — calling for the resolution of their long-running dispute. Wang Jingli / for China Daily

A scene of "chaos" greeted Charlie Winstanley as he arrived at his local A&E in England, nursing suspected broken ribs.

"A packed, tense waiting room, with more than 100 patients ahead of me, and a seven-hour waiting time projected to worsen as the night went on," he wrote in Tribune, a political magazine founded in 1937 and published in London, as he described the experience. "People stood without chairs, others sat in clear distress, and few new names were called. Frazzled staff barked instructions as they struggled to cope."

Fresh announcements warning of longer delays echoed through the room. The waiting time had risen to nine hours. Tempers frayed. In the end, patients — including an elderly man with a heavily bleeding facial injury and a woman with a severe limp — began to "self-discharge", as it became clear there was only one consultant on duty and too few doctors to make clinical decisions.

"It was an experience thousands across Britain now recognize: overwhelmed staff, failing systems, and a level of disorganization that has quietly become the norm," he wrote.

The National Health Service, or NHS, is often hailed as a crown jewel of British culture for its universal, cradle-to-grave, and free-at-the-point-of-delivery system. Yet, on its 75th birthday in 2023, David Oliver, an NHS doctor for 34 years, wrote in the British Medical Journal that the service faced "an existential crisis as bad as at any time since (it) was founded".

Currently, the crisis is a prolonged dispute between medics seeking better pay and the government.

On Dec 1, the British Medical Association, or BMA, announced resident doctors in England would strike again this month, in the run-up to Christmas, starting a five-day walkout at 7 am on Dec 17.

This latest round of industrial action will be the 14th time resident doctors have walked off the job since March 2023 and follows a five-day strike in November.

A last-ditch government offer, which included no new pay promises but a proposed doubling of the number of extra specialty training posts to 4,000 in a bid to ease doctors' unemployment worries, was overwhelmingly rejected via a BMA indicative poll.

It came as the NHS warned it is facing its "worst-case scenario" for flu cases. Hospitalizations because of the flu surged by more than 50 percent in the first week of December and officials warned there was no sign of it peaking.

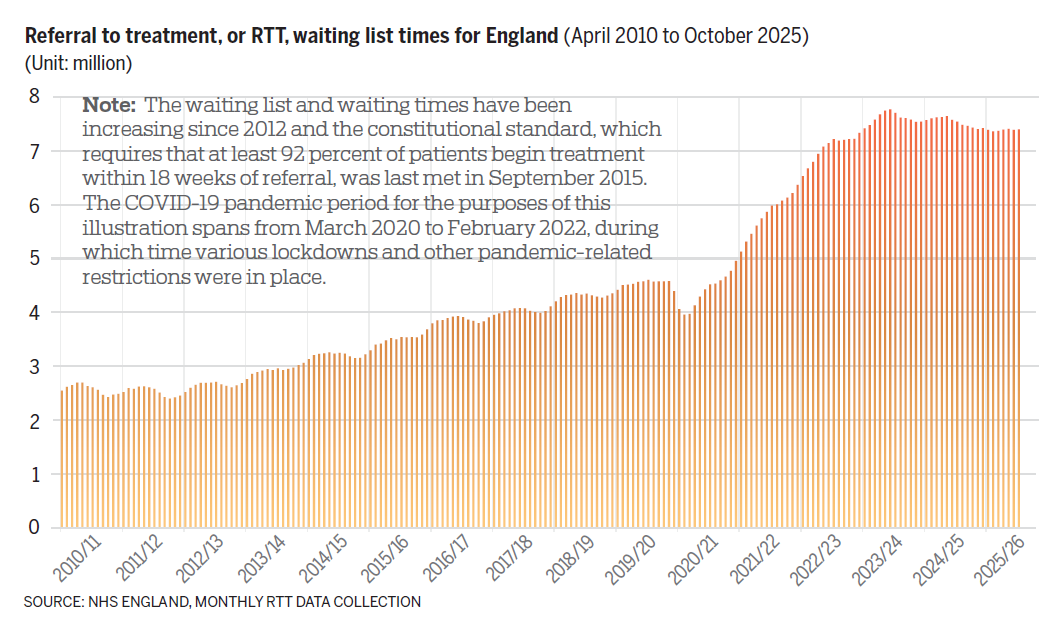

Meanwhile, the waiting list for hospital treatment stood at 7.4 million in October, with 172,556 of the cases involving patients who had been waiting for more than a year, according to NHS England.

"I believe in workers' right to strike," UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer said. "But the strikes … planned by resident doctors should not happen, they place the NHS and patients who need it in grave danger."

Jack Fletcher, co-chair of the BMA resident doctors committee, dismissed the government's latest proposal as "too little" and "too late" and said doctors "have no choice" but to return to the picket lines.

Resident doctors make up around half of the UK's medical workforce. Formerly known as junior doctors, they tend to be relatively recently qualified medical practitioners who are in the process of training toward a specialty, which can take a decade or more.

An estimated 38,500 outpatient appointments and treatments — including surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy for cancer — had to be rescheduled because of the last walkout, The Guardian newspaper reported.

Wes Streeting, the UK's health minister, has accused the BMA of having "juvenile delinquency" and resident doctors of being "moaning minnies" in response to the latest strike announcement.

Asked if patients are going to die because of the latest strike, Streeting told Sky News: "I don't want to be catastrophic about it, but it is a different order of risk, and I am genuinely worried."

Tug-of-war

Pay has consistently been the focal point of the long-running tug-of-war between the government and the union.

"The pure fact that there have been 13 rounds of strikes, just by that itself tells you that it is not a simple issue," said Sam Liu, an NHS consultant cardiologist and medical director at MEDii Health, a London-based private hospital.

The UK government has highlighted the fact that resident doctors have had an average increase in pay of 28.9 percent over the last three years, factoring in the 5.4 percent rise agreed this May.

Currently, resident doctors at different levels of seniority earn between 38,831 pounds and 73,992 pounds ($52,146 and $99,363) a year for a 40-hour week. When comparing doctors' pay with salaries across the wider economy in England, average total earnings for first-year doctors — the most junior level — is above the median, so above the halfway point for all workers' pay, the Nuffield Trust health think tank found in its July explainer.

Total earnings consist of the basic salary and also extra payments covering, for example, on-call duties, night shifts, weekend work and payment for working longer hours, as well as geographical allowances.

These figures have confused — or even irritated — members of the public, with comments on X under BMA strike-related posts saying doctors are asking for too much.

Some people have even argued that doctors' right to strike should be "taken off" them.

"You are there to save lives," one comment said. "You should not be able to strike, it's as simple as that."

Opposition to the resident doctors' strikes has reached a record high, according to the latest YouGov polling, with 53 percent of the British public against them.

That said, Amie Brillu-Ogden, a Briton who lives in Bath, said she supports the strikes because resident doctors are not being paid enough.

"Inflation has been tough, and all public servants should be getting an increase of more than inflation; otherwise, they are essentially getting a pay cut," she said. "I don't believe the strikes are the reason the system has deteriorated. Often, they are used as a scapegoat to deflect responsibility from the government."

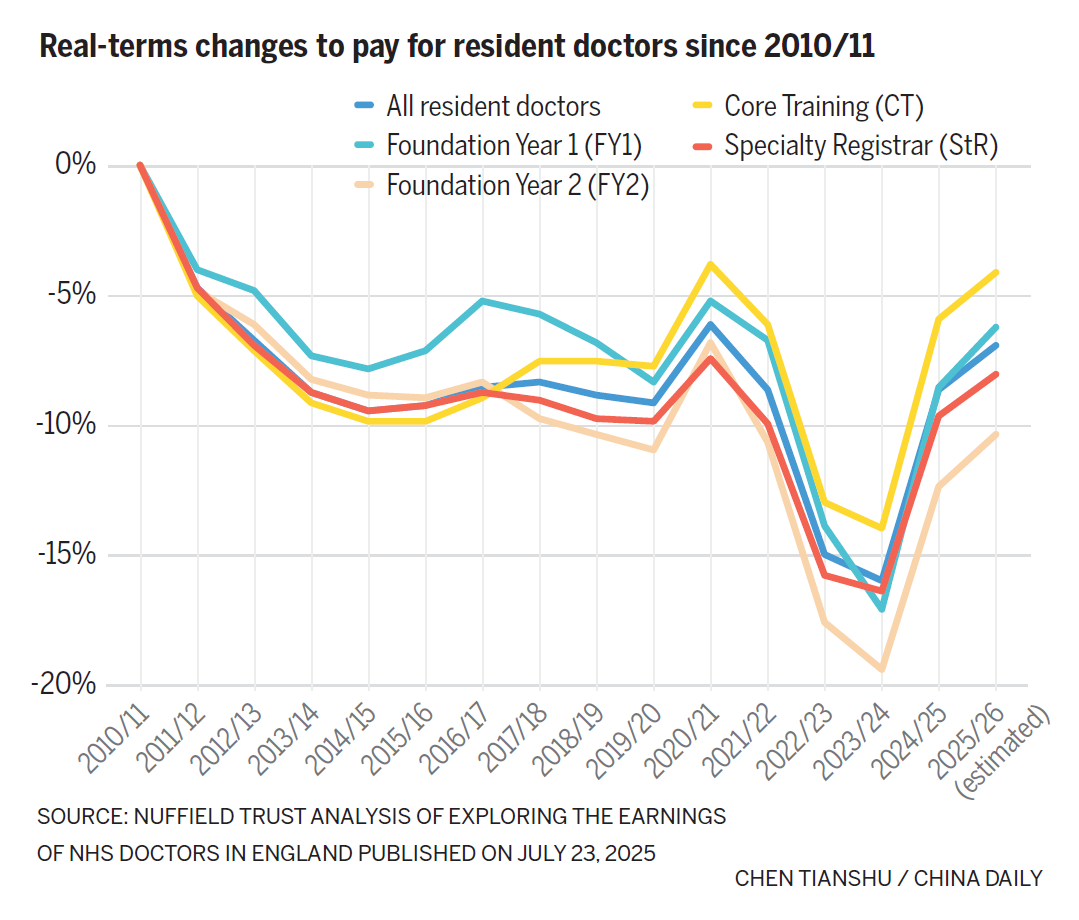

The BMA has argued that resident doctors' basic pay is 20 percent lower in real terms than it was in 2008, even after the 2025 increase. Real terms figures are adjusted for inflation and reflect the true value of money in terms of what it can buy. Doctors say pay rises since 2008 simply have not kept up with the rising cost of living.

The Nuffield Trust explainer estimates that average real-terms earnings for 2025-26 have eroded by between 4 percent and 10 percent since 2010-11.

Pay analysis can be endlessly contested. The choices of baseline year, the way inflation is calculated, and other data can create very different pictures.

For example, measured against the consumer price index, or CPI, resident doctors' pay has fallen by just 1.6 percent since 2010. But when using the retail price index, or RPI, it has decreased by 15.5 percent, a Nuffield Trust analysis noted.

The government uses the CPI for its calculations, which is also an internationally recognized method. Trade unions, including the BMA, prefer using the RPI as a measure of the actual affordability burden felt by working people, because the RPI captures housing costs, as well as student loan interest costs, which are important to many doctors.

The RPI lost its status as a national statistic back in 2013.

The UK Office for National Statistics, or ONS, said: "Our position on the RPI is clear: we do not think it is a good measure of inflation and discourage its use."

The BMA is demanding a multi-year pay deal toward "full pay restoration", which would amount to a 26 percent rise in basic rates on top of the 28.9 percent increase already received.

Is that achievable? Liu said it "depends on practicability". The Nuffield Trust estimates a 1 percent uplift for resident doctors in 2025-26 would add roughly 51 million pounds to the NHS wage bill.

"What I can say is that it is not really about pay; it is about a trifecta of issues that resident doctors are not happy with," Liu said. "People like to talk about pay because people understand it. But two other very important factors are less talked about and less understood: career progression and rota gaps."

Bottlenecks

Many resident doctors cannot go on to train in specialties after they finish their first two years as foundation doctors because there are not enough places in the programs, Liu said.

This year in the UK, more than 30,000 applicants competed for around 10,000 places, according to the BMA, which said the unemployment crisis not only stunts resident doctors' careers but also deprives the NHS of the workers it needs to reduce waiting list.

"In some years in cardiology, there were only two places in the whole of London," Liu said. "People came in. They knew at the age of 16 they wanted to be a brain surgeon or a gynecologist. They just can't do that … You simply cannot get into the specialty, and that takes people's passion away."

Meanwhile, the NHS has been short-staffed on a daily basis, and resident doctors face an intensifying workload to cover rota absences, Liu said.

The BMA said back in 2018 that 70 percent of resident doctors reported working on a rota with a permanent gap, and more than two-thirds of medical professionals had been asked to act up into more senior roles to fill the gaps.

A patient receives a Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine in 2021 at a mass vaccination center at Tottenham Hotspur Stadium during the COVID-19 pandemic. Photo / Agencies

An estimated 100,000 vacancies in the NHS are currently unfilled, according to a November analysis by the healthcare charity, the King's Fund.

"Although the workforce has been growing, demand for the service has been growing faster, and the health service has not been able to recruit and retain sufficient staff to shrink the number of vacancies," it said.

It all then spirals into a "vicious cycle", Liu said. Rotas have been shrunk to reduce the number of doctors, without reducing the workload. Resident doctors scramble to cover absences, patients keep calling, consultants check in, and the whole grind repeats, sometimes, it even gets worse. The process wears down resident doctors' psychological and social lives until some burn out, forcing colleagues to step in and take more strain.

"That is why they said enough is enough. We need to gather attention and let people know this cannot be carried on," he said.

Due to strikes, many elective operations, outpatient appointments, and tests will need to be canceled, extending the already lengthy waiting lists, but the back-to-back actions also "demoralize the workforce", as circular bargaining erodes goodwill, and trust between doctors and the government, Liu said.

"When people strike, they don't get paid," Liu said. "They are not doing something they actually want to do, which is looking after patients and getting trained … A lot of them (already) don't get trained because of rota gaps.

"What we've talked about takes a little bit of time to appreciate. How — as a government, as a member of society — we are going to look after the next generation of doctors who are going to look after you and me. How would you like them to be treated … so that they feel that they are rewarded, secure, valued, so that they love their jobs?

"A happy doctor will do a happy job. A stressed, depressed, undervalued, and overworked doctor will make mistakes. And as a result, patients and society suffer."

What's ahead?

Spending on the NHS after inflation has risen by nearly a fifth, and the workforce by almost a quarter, compared to five years ago, the BBC reported in 2024, yet the number of patients starting treatments has barely increased.

Brillu-Ogden even said she feels like the NHS "is declining more than ever" with the system becoming "reactive" rather than "proactive", mainly responding to already-developed symptoms. The long waits to get in front of a medic often means treatment can come too late.

A core, and far simpler, answer is that "the NHS was not designed to look after the current size of population", Liu said.

The population of the UK continued to grow in the year to mid-2024, reaching an estimated 69.3 million people, the ONS reported in September. The rate of growth has also been higher in recent years, with the rise seen in the year to mid-2024 marking the second-largest annual numerical increase for more than 75 years.

The UK population is also aging, which in some ways reflects the success of the NHS, because people now live for longer, Liu said. But that means they also have a longer list of medical issues requiring care.

"The NHS is said to be a victim of its own success because the more successful you are, the more pressure you have," Liu pointed out. "These are multilayered demands on the services … and the demands are rising faster (than investment). As a result, it is proportionally less equipped to deal with the increasingly expanding problems."

There is still room to improve, Liu said. An integrated medical record system would save doctors significant time spent contacting different hospitals to gather patient charts. More focus could be placed on preventative healthcare as a way to reduce pressure; educating the public about sugar addiction, excessive carbohydrate intake, issues related to weight, and cancers.

But massive problems rarely come with straightforward shortcuts to solutions, Liu said.

For him, the NHS has, so far, been relying on the "goodwill" of everyone in the system, the majority of whom are "overworked".

Gao Kejing and Wang Jingli contributed to this story.

Contact the writer at zhengwanyin@mail.chinadailyuk.com.

A resident doctor holds a banner on Wednesday on the picket line at St Thomas’ Hospital in London, England. Kirsty Wigglesworth / AP