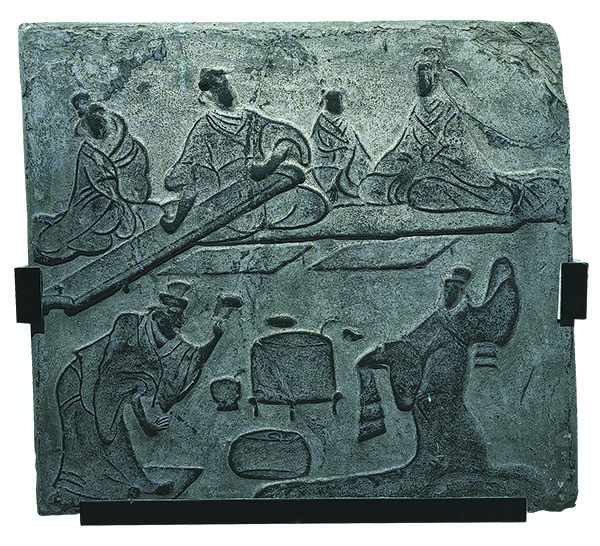

Zithers and Flutes of the Brocade City, an exhibition at Chengdu Museum, in Sichuan province, celebrates the city's music tradition, gathering artifacts such as a stone relief depicting musicians of the Song Dynasty (960-1279). [PHOTO BY HUANG LERAN/FOR CHINA DAILY]

Chengdu Museum's special exhibition highlights artifacts that have the power to fascinate, Huang Zhiling and Peng Chao report.

Renate, a senior citizen from Cunha in Brazil's southeastern state of Sao Paulo, visited the Chengdu Museum in Southwest China's Sichuan province with her husband Arpad on March 15.

It was the couple's first visit to China and they arrived to explore the city's storied past and culture in the museum in the heart of Chengdu, the provincial capital.

Yet they had a pleasant surprise of finding themselves transported further back in time through a special exhibition in the museum featuring ancient musical treasures from different parts of China, according to Renate, a former nature photographer.

The special exhibition, titled Zithers and Flutes of the Brocade City, which runs through to May 5, is a collaborative effort by more than 30 institutions, including the Henan Museum in Central China's Henan province, the Palace Museum in Beijing, Dunhuang Academy in Northwest China's Gansu province, Yungang Grottoes Academy in North China's Shanxi province, the Shaanxi History Museum and Emperor Qinshihuang's Mausoleum Site Museum in Northwest China's Shaanxi province, says Huang Xiaofeng, deputy curator of the Chengdu Museum.

The showstopper, positioned in the most prominent place in the exhibition hall, is an 8,000-year-old bone flute unearthed in 1987 at the Neolithic Jiahu Site in Wuyang county, Luohe, Henan province.

This 23.1-centimeter artifact, on loan from Henan Museum, is among 88 national first-class cultural relics on display in the special exhibition.

Zithers and Flutes of the Brocade City, an exhibition at Chengdu Museum, in Sichuan province, celebrates the city's music tradition, gathering artifacts such as a pair of whistleblowing pottery figurines dated to about the fourth century. [PHOTO BY HUANG LERAN/FOR CHINA DAILY]

In the history of Chinese archaeology, the Jiahu Site dating back 7,800 to 9,000 years was one of the most developed ancient settlements in its time.

It was in the Neolithic Age.

Then, humans had just come out of caves and were clumsily trying to grow plants and breed domesticated animals.

But Jiahu shows a picture that is not completely primitive and backward, and transcends people's understanding of the initial stage of civilization.

Han Jianye, an archaeology professor at Renmin University of China in Beijing, says the origins of Chinese civilization was formed around 8,000 years ago, and the most shocking and direct evidence is Jiahu.

The production of pottery, bone ware, turquoise, especially the excavations related to the astronomical calendar and divination, had a great impact, he says.

Between 1984 and 2001, Jiahu witnessed the excavation of more than 30 flutes made from the wing bones of red-crowned cranes.

The Jiahu bone flute, on display in the Chengdu Museum, is shaped like a long pipe with seven holes drilled in a straight line down one side.

It is the earliest musical instrument unearthed in China, and it is also recognized as the earliest playable musical instrument in the world.

The delicate and small flute astonishes contemporary researchers as it is capable of playing the seven-tone scale.

In the opening ceremony of the special exhibition on Jan 21, a local musician used a homemade bone flute to play music.

Hearing the music was like catching whispers from a primordial dawn, said Lan Mei, a visitor who noted how the flute's haunting tones might have once echoed in ancient rituals.

The special exhibition's timeline leaps to the Tang Dynasty (618-907) with a 1,311-year-old guqin (a plucked seven-string Chinese musical instrument) from East China's Zhejiang Provincial Museum.

It was crafted by guqin master Lei Wei in 714, and was an imperial wedding dowry.

With a coating of vermilion lacquer and adorned with ice-crack patterns, the long zither got its lyrical name, Caifeng Mingqi, from the ever-changing glow of the sunset and the consonant cry of a phoenix.

Its producer Lei Wei had the reputation of being "China's No.1 luthier".

A Tang Dynasty (618-907) stringed guqin draws the audience. [PHOTO BY HUANG LERAN/FOR CHINA DAILY]

In the Tang Dynasty, a Lei family in Sichuan was known for making guqin masterpieces, and Lei Wei was the most famous in the family.

Legend has it that Lei Wei would run to the mountains and ancient forests on snowy days when he was drunk.

As the north wind howled and shook the trees, he listened to the resonant sound of the branches — a poetic approach to selecting good materials for guqin production.

The guqin is 124.8 cm long with three kinds of timbres: overtones, press tones and scattered tones, symbolizing the harmony of heaven, earth and man.

According to Tang Fei, head of the Sichuan Provincial Cultural Heritage Administration, this is its first homecoming to its birthplace of Sichuan.

A Tang Dynasty stone statue of a pipa player. [PHOTO BY HUANG LERAN/FOR CHINA DAILY]

Rare artifacts which captivate visitors to the special exhibition abound, including a wooden pipa (lute) in the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms (907-960) period, from the Yangzhou Museum in East China's Jiangsu province, and a fresco, from the Shaanxi Archaeology Museum, which shows ancient women musicians playing konghou (an ancient plucked, stringed instrument).

There are a bronze chime bell, made in the Song Dynasty (960-1279) and collected in Hebei Museum in North China's Hebei province, and a brick depicting musicians which is from the Gansu Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, in Gansu province.

"All of them are being shown in Sichuan for the first time," says Wang Li, an information officer in the Chengdu Museum.

The pipa is the only wood-carved musical instrument unearthed in the archaeological history of China, according to the Yangzhou Museum.

A smiling pottery dancer of the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220). [PHOTO BY HUANG LERAN/FOR CHINA DAILY]

Yet to many ordinary visitors, few delights in the special exhibition can rival a smiling pottery woman dancer, made in the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220), which is in the collection of the Chengdu Museum.

Since Li Bing, then a governor of Sichuan, built the Dujiangyan Irrigation Project around 256 BC, the Chengdu Plain has had no major floods or drought. With fertile land and grain harvest, it is known as the land of abundance.

Visitors who have seen the smiling pottery dancer would joke that Chengdu people were satisfied with their life 2,000 years ago.

Contemporary Chengdu people are also noted for their fondness for drinking tea, playing mahjong and having a positive attitude of life.

Renate was most impressed with a smiling pottery rap musician in the Eastern Han Dynasty.

It is in a standing position, its posture is exaggerating, and its expression is very humorous, she said, showing a picture of the musician on her phone.

According to Wang, there are so many Eastern Han Dynasty smiling pottery figurines in the collection of her museum which are yet to be counted.

Potteries of the Southern and Northern Dynasties (420-581) period. [PHOTO BY HUANG LERAN/FOR CHINA DAILY]

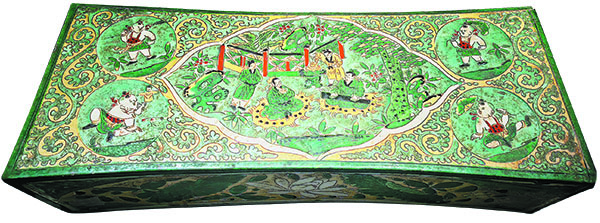

A Song Dynasty pillow. [PHOTO BY HUANG LERAN/FOR CHINA DAILY]

A painted terracotta brick ( huaxiangzhuan) of the Eastern Han Dynasty shows a feast. [PHOTO BY HUANG LERAN/FOR CHINA DAILY]