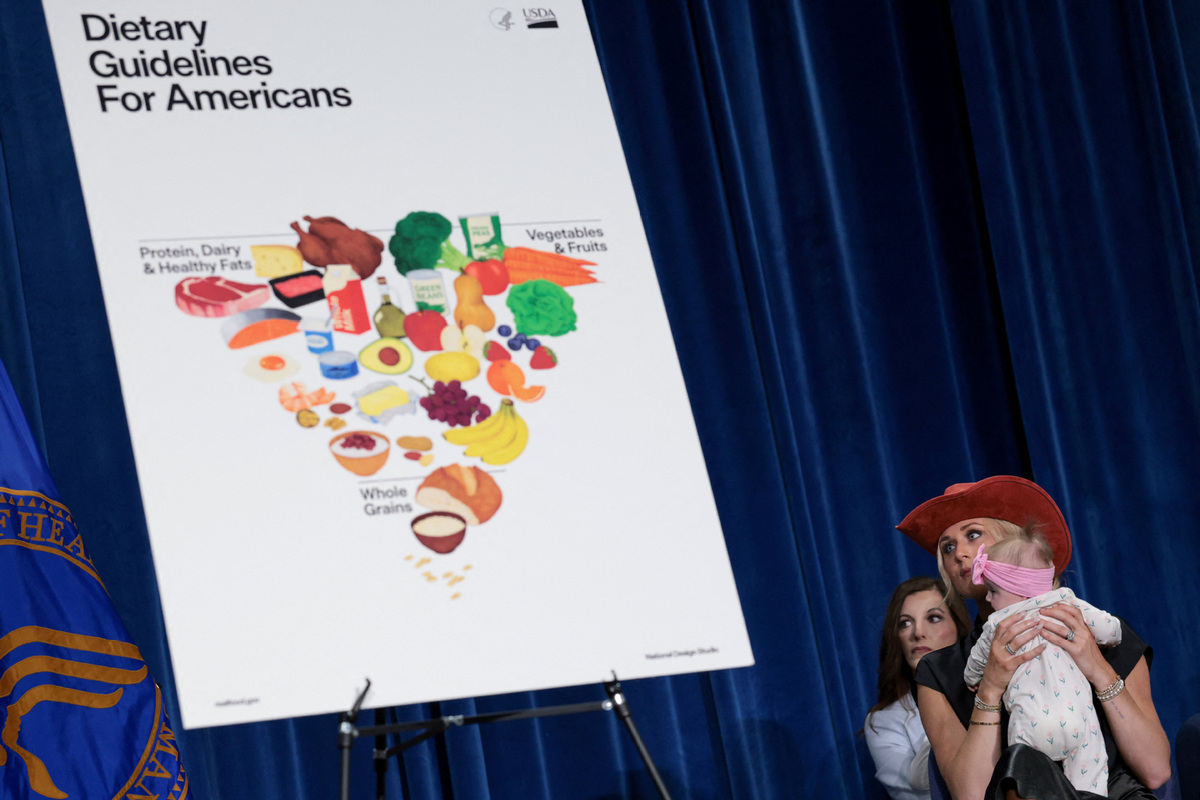

Riley Gaines, US conservative political activist holds a child, on the day US Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins (not pictured) announce new nutrition policies, during a press conference at the Department of Health and Human Services in Washington, DC, US, Jan 8, 2026. [Photo/Agencies]

When health officials in the United States unveiled new dietary guidelines earlier this month, they framed the announcement as a call to eat more "real food" and fewer ultra-processed products. However, the new guidelines place meat, full-fat dairy products and oils at the foundation and center of the food structure, while pushing grains and fruits to the margins, setting off alarm bells among nutrition experts and drawing close scrutiny from China.

Released jointly by the US Departments of Agriculture and Health and Human Services on Jan 7, the new guidelines are a sharp departure from decades of federal nutrition advice. Among other things, the guidelines remove a recommended daily limit on alcohol consumption.

US officials said the update reflects a growing consensus that Americans should prioritize protein and minimally processed foods over refined carbohydrates and packaged snacks. Critics, however, argue that the changes are confusing, poorly supported by evidence and could have been shaped by political pressure, BBC News reported.

"They claim this is based on scientific evidence," said Marion Nestle, a professor emerita of nutrition at New York University, but when asked if the evidence is enough to promote eating more meat and high fat dairy, she said it's "hard to know".

The release has revived a familiar fight over US nutrition policies, with a question lingering like chronic heartburn: Who are the guidelines supposed to serve?

Protein consumption in the US already exceeds recommended levels for most adults, according to several nutrition researchers. Now, eating even more of it risks worsening chronic problems without addressing deeper troubles in the food supply system.

The debate has resonated far beyond US borders. In China, nutrition experts have been analyzing the eye-popping implications.

"Dietary guidelines don't just affect what's on the plate," said Gu Zhongyi, a prominent Chinese dietitian. "They reshape agricultural supply chains, land use and food prices."

China's official dietary guidelines continue to emphasize grains as a foundation, with moderate amounts of fats and protein. Gu said that approach takes into consideration both nutritional evidence from Chinese populations and the realities of domestic food production.

"What suits China better is improving protein quality, not dramatically increasing protein quantity," he said. "Soy products, poultry and eggs are more sustainable and accessible."

Ruan Guangfeng, a Chinese nutrition researcher, said that the 2022 revision of dietary guidelines by the Chinese Nutrition Society was based on a comprehensive survey of changes in the health of Chinese people in recent years.

The survey adhered to the principles of nutritional science and the latest scientific evidence, Ruan said, while also taking current requirements into account such as the need to prevent and control pandemics and reduce food waste.

The US now recommends the equivalent of 72 to 96 grams of protein per day for a person weighing 60 kilograms. But for the general population, consuming excessive protein without adequate physical activity can increase metabolic burden on the kidneys and raise the risk of kidney diseases, Ruan said. The estimated average daily protein intake of a Chinese person is about 62 grams, which meets government recommendations.

"Some of the revisions in the US appear to reflect bargaining by interest groups rather than new scientific breakthroughs," Ruan said.

Environmental advocates have also questioned why the new guidelines largely ignore climate considerations. Dietary choices not only concern individual health but also affect the ecological balance and the use of land and water resources.

Zhang Qinglu, a researcher at Huazhong Agricultural University in Wuhan, Hubei province, said: "From a macro perspective of agricultural supply, the dietary structure proposed by the new guidelines fails to account for its implications on agricultural burdens, and its effects on global ecological sustainability remain subject to debate."

Therefore, whether it holds "universal applicability and can be adapted to diverse populations and nations requires further investigation", he added.

Eating more meat and dairy is not realistic for a lot of families, said Jimmy Zhang, a Chinese restaurant owner in Boston, Massachusetts. "All of us would like to eat better, but we still have to pay rent."

Among ordinary Chinese residents, there is curiosity and caution. "I see a lot of fitness influencers talking about high-protein diets in the US," said Li Wen, a 42-year-old teacher in Wuhan. "But doctors still tell us to eat more vegetables and whole grains, and I'll follow their suggestions."

According to Li, avoiding heavily processed food surely is good, but "balance is the key".

Liu Kun in Wuhan contributed to this story.