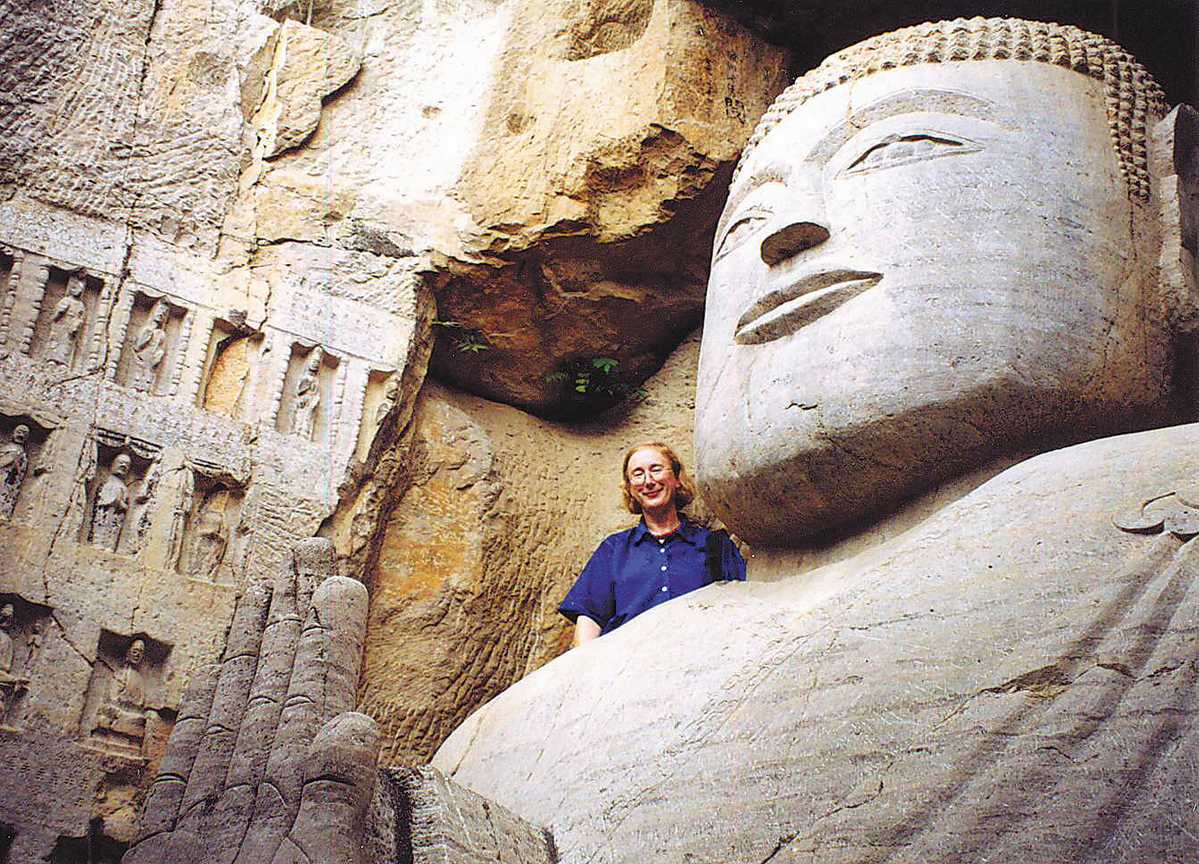

Jessica Rawson visits the Baifoshan Grottoes in Dongping county, Shandong province, in 1999. PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY

Editor's note: China Daily presents the series Friends Afar to tell the stories of people-to-people exchanges between China and other countries. Through the vivid narration of the people in the stories, readers can get a better understanding of a country that is boosting openness.

China is very, very different. Jessica Rawson repeatedly underlines this point.

This idea might seem obvious, but she believes that people often underplay the divergence that China inherits.

"The big trouble is Westerners don't think they need to study China. They think, if China had a past, it would be like the Greeks, the Romans, or something they're familiar with here," she says. "The West doesn't really notice China, doesn't understand the difference, doesn't understand why your culture is not like ours."

Rather than digging into the similarities we share, recognizing how ancient China charted its unique course may lead to adjustment, and then better mutual understanding, she argues.

For the 82-year-old archaeologist, who is a former keeper of the Department of Oriental Antiquities at the British Museum — one of her many titles, her career over the past 50 years has been consistent: China's distinctive path of development, explored through the eyes of objects, like ceramics, jades and bronze vessels.

By looking into China's material culture, Rawson has provided a new perspective on one of the world's oldest civilizations, uncovering the values, beliefs, and customs embedded in the shapes, colors and motifs of its remains.

China's distinctiveness was revealed to Rawson long before she set foot in the country.

During a trip to the British Museum at the age of 10 or 12, the Rosetta Stone, inscribed with Egyptian hieroglyphs — a writing system that used pictures as signs — taught her that there is a language in the world not based on alphabetic letters.

"Why not look at Chinese if you're interested in this," her parents said and then gave her a small book called Teach Yourself Chinese.

"When you're 12, you can't teach yourself Chinese," she jokes. "But I started to copy the Chinese characters into a notebook."

"Pioneering" is a word often associated with her and her approach to looking beyond and looking around was described as "Rawsonian" by Robert Harrist Jr, professor of Chinese art history at Columbia University in the United States.

And she has been determined to study Chinese archaeology and get inside the cosmology of others.

"I've dedicated my entire life to this field," she has written in a letter. "There had been a few resistance along the journey, but I have never thought of giving up."

"Since the Neolithic era, China's developmental path has been uniquely its own. Throughout my academic career, I have increasingly recognized the importance of introducing more people to China's history and the latest results in archaeology. Only by doing so can they cultivate a genuine interest in China."

Language of objects

In 1968, when Rawson joined the British Museum, she was tasked with cataloging thousands of ceramics and jades from the Shang (c.16th-11th century BC), Zhou (c.11th century-256 BC) and Han (206 BC-AD 220) dynasties — relics she found "very surprising" at first sight.

Seeing some objects as "China's greatest works of art", Rawson found that those exquisite things are often not vehicles for self-expression but functional forms for ancestor worship, crafted according to strict standards dictating their shapes, patterns, and decorations, exemplified by bronze vessels.

She wondered why the Chinese were so obsessed with this particular type of object, but not gold or gems. Breaking it down step by step, what stands out to Rawson is that the ancients' fascination with bronze vessels reveals the distinctiveness of China, from its climate and terrain to the cosmology of the inhabitants.

The Loess Plateau in north-central China once buried the ores or metals under layers of heavy windblown dust. The mining alone required an immense workforce, not to mention the demanding craftsmanship needed to smelt and cast even a single piece, which explains why bronze vessels were mostly evacuated from the tombs of royalty and nobility, Rawson says.

Life and the afterlife in China unveil fundamental differences in the nation's ancient society, in how the ancestors were treated as being at the top of a generational hierarchy, and how families, united by shared ancestry and kinship ties, became central, she says.

In her latest book Life and Afterlife in Ancient China Rawson explores 12 grand tombs and a major sacrificial deposit from across China.

The "master interpreter", as the former director of the National Gallery in London and British Museum Neil MacGregor describes Rawson, never treats an object in isolation but traces down to the usage, customs, and beliefs — shaped by climate and geology — all pointing to why the Chinese are not like Westerners or anyone else in the world.

While China is fascinated with bronze, the West prizes gold and gems. While the Chinese eat rice from ceramic bowls, the West uses plates for salad. What Rawson believes is that every culture develops its material system.

There are no shortcuts for a foreigner to study Chinese archaeology, Rawson once said.

In 1975, she set foot in China for the first time. It was a time when the country only owned trains in green that chugged her through the vast landscape, from the plains with fields of rice to the endlessly stretching plateau.

"It's a shock to realize how big China is, how many regions are different from each other, and how they're all different from the West and, above all, from Western Asia," she says.

To truly get an impression of the place, the only way is by traveling it, she believes. For the next 44 years, Rawson returned to China nearly every year, traveled alone sometimes, and even once slept at a train station to catch the earliest service.

"China is not a quick thing to learn," Rawson says. But she did not give up trying to get closer to that dream path. "I always wanted to work in China. In a way, people would say I am always addicted to China. I am happier thinking about China or reading about China than doing anything else."

What might be more difficult is introducing what sets China apart from the West, Rawson admits, yet she remains committed to doing so.

As the British Museum stands as one of the most-visited attractions in the UK, the former keeper prioritized her work, especially the refurbishment of the China Gallery, both in 1992 and 2016, as a top priority.

Her career as a curator did not mark a break, even after leaving the museum. She continued to curate blockbuster China-related exhibitions in the UK, such as China: The Three Emperors, 1662-1795, which was opened by Queen Elizabeth II in 2005 at the Royal Academy of Arts in London.

During her years at the University of Oxford, a major grant by the Leverhulme Trust, which she bid on and received, not only supported the founding of a contemporary China studies program in 2002 but also led to the creation of a China center in 2008.

Her efforts to promote exchanges somehow mirror another of her research achievements — the interactions in ornament culture between China, Inner Asia, and the West. While China's path has been independent, it has never been completely isolated, and "we need to see how much we get from each other," she says.

zhengwanyin@mail.chinadailyuk.com