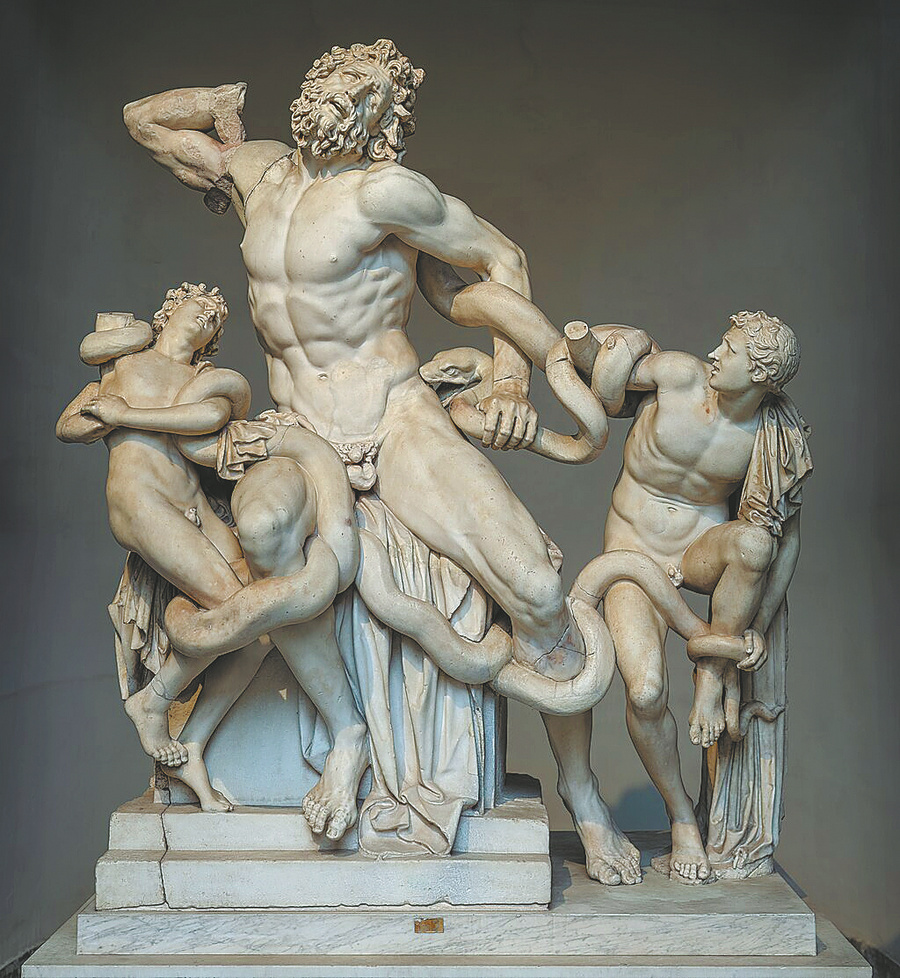

The Hellenistic sculpture Laocoon and His Sons captures the agonizing moment when the Trojan priest and his sons are ensnared by sea serpents. VATICAN MUSEUMS

According to one version of the ancient Greek mythology, Hermes, the messenger god who was also the deity of commerce, travelers and boundaries, once encountered two snakes fighting. Using a staff, he separated them, and the snakes coiled around the staff in perfect balance, transforming themselves, together with the rod itself, into a symbol of harmony and peace befitting Hermes' role as a mediator.

Caduceus — that's the name of Hermes' rod, a staff with two intertwined snakes and wings, which the god, known as Mercury in Roman mythology, carried around to ward off disputes and bring about reconciliation.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York owns an 18th-century oil painting depicting Cupid, barely covered in pink drapery, holding a caduceus — the symbol of his father, Mercury.

While few may have associated snakes with the art of diplomacy, let alone with a chubby baby, many have confused the caduceus with the Rod of Asclepius, a staff entwined with a single snake that symbolizes healing and medicine.

Gliding seamlessly through ancient Greek and Roman mythology, the snake found its presence intricately woven into the literary tapestry by masters such as Ovid (43 BC-AD 17) and Virgil (70-19 BC), both Roman poets who lived during the reign of Emperor Augustus. To them, the serpent became a potent symbol, embodying divine wrath, prophetic insight, the inescapability of fate, and the complexities of human nature.

In his world-renowned narrative poem Metamorphoses, Ovid told what's perhaps the most famous serpent-related myth — the tragic story of Medusa, a beautiful mortal priestess in Athena's temple.

An Augustan Roman marble copy of the head of Medusa. GLYPTOTHEK MUSEUM IN MUNICH

In Ovid's Roman retelling of the Greek myth, Poseidon, the god of the sea, desired Medusa and raped her in Athena's temple, violating the sacred place. Enraged by the desecration of her temple, Athena, instead of punishing Poseidon, directed her wrath at Medusa, transforming the poor girl into a Gorgon, a monstrous figure with snakes for hair and a gaze that turned anyone who looked at her to stone. As if to add another layer of poignancy and irony to Medusa's fate, she was later slain by Perseus, a hero in Greek mythology who gave her severed head to Athena to be placed on the shield of the goddess as a protective emblem.

Later-day interpretations of Medusa's story continue to evolve, reflecting shifting cultural understandings. Modern readers and scholars often see her tale as a commentary on the injustice faced by women in both mythology and society. Some, however, interpret Athena's actions — though harsh — as an attempt to shield Medusa from further harm, granting her a mournful form of empowerment.

Divine wrath invariably exacted a heavy toll. In Virgil's Aeneid, Laocoon, a Trojan priest, warned his countrymen against bringing the wooden horse into the city, uttering the famous line: Timeo Danaos et dona ferentes ("I fear the Greeks, even when they bring gifts"). His warning was ignored. The massive wooden horse, constructed by the Greeks with a hollowed-out interior to conceal their elite soldiers, was welcomed into the city as a peace offering. At night, the Greek soldiers emerged from the horse, opening the city gates to the returning Greek army, leading to the fall of Troy.

Yet, Laocoon didn't even have the chance to witness that fall — as punishment, he and his two sons were strangled by two enormous sea serpents sent by gods who supported the Greeks. In 1506, a statute of Laocoon and His sons was excavated in Rome and put on public display in the Vatican Museums, where it remains today.

An 18th-century canvas depicting Cupid. THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART IN NEW YORK

Dated to a time period between the 2nd century BC to the 1st century AD, the sculpture, capturing the harrowing, hopeless moment when the serpents crush the three in their coils and kill them in a horrifying spectacle, vividly conveys the full impact of divine retribution.

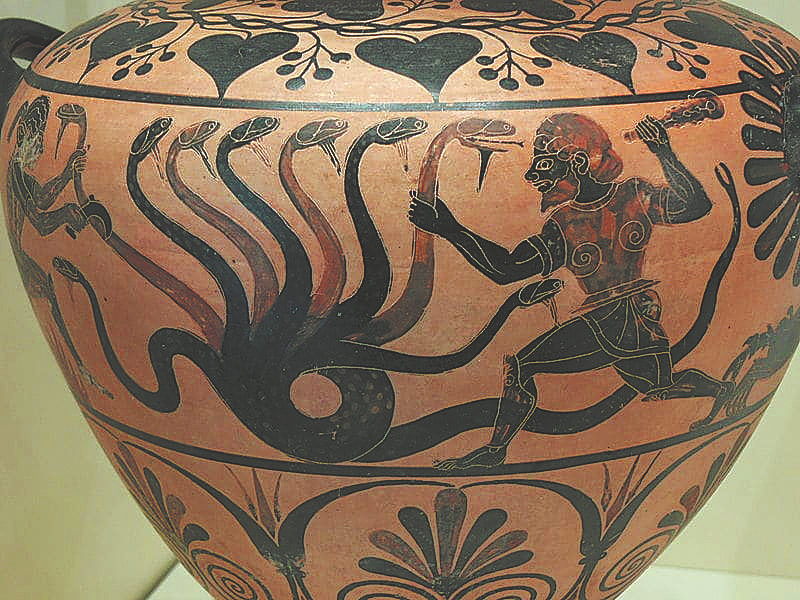

Elsewhere, Heracles, the son of Zeus and the greatest of all Greek heroes, vanquished the Hydra, a multiheaded serpent — a feat frequently depicted on ancient Greek vases.

Given the snake's connection to the earth, it is unsurprising that these creatures are linked to Hades, the god of the dead and ruler of the underworld. The symbolism is also embodied by Caduceus, the staff held by Hermes, who, in his many roles, also served as a herald to the underworld.

Another story linking the snake to a magical staff appears in the biblical narrative. In the Book of Exodus, when God called Moses to lead the Israelites out of Egypt, he provided miraculous signs to confirm his divine authority. One such sign involved Moses throwing his staff on the ground, where it became a serpent. When Moses picked it up by the tail, it turned back into a staff, demonstrating that God was with him.

Later, when the Israelites journeyed through the wilderness after their exodus from Egypt, the great hardship facing them led many to speak against God and Moses. As a consequence of their ingratitude, God sent venomous serpents among the people, and many were bitten and died. The people, realizing their sin, repented and asked Moses to intercede on their behalf.

In response, God instructed Moses to make a serpent out of bronze and mount it on a pole. Anyone who had been bitten could look at the bronze serpent and would be healed. "The brazen serpent", with brazen historically used as a synonym for bronze, represented healing and salvation through faith in God's provision.

An ancient Greek vase featuring a scene of Heracles slaying the Hydra, the multiheaded snake. THE J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM IN MALIBU

The snake in the Garden of Eden, which tempted Eve to eat the forbidden fruit from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, is traditionally viewed in the West as a force leading humanity to question and defy God's command.

By eating the fruit, Adam and Eve claimed the divine prerogative, asserting the right to define good and evil for themselves rather than trusting in God's wisdom.

This act of moral autonomy brought with it the burden of moral responsibility and what is often referred to in the biblical context as the "loss of innocence". Consequently, some modern interpretations, while acknowledging the view of the snake as a source of temptation in the Judeo-Christian tradition, see it less as purely evil and more as a catalyst for human agency and free will.

In fact, the snake's connection to the Tree of Knowledge is tied to its role as a guardian — of kings and gods, temples and tombs, treasures and knowledge — as well as its mysterious and ancient nature, which has long been associated with wisdom.

In the Gospel of Matthew, the first book of the New Testament of the Bible, Saint Matthew, one of the 12 apostles of Jesus Christ who's credited as the text's author, encouraged the believers to be discerning while maintaining moral purity.

"Be wise as serpents and innocent as doves," he said.