A sculpture of Asclepius, the Greek god of healing and medicine. CHINA DAILY

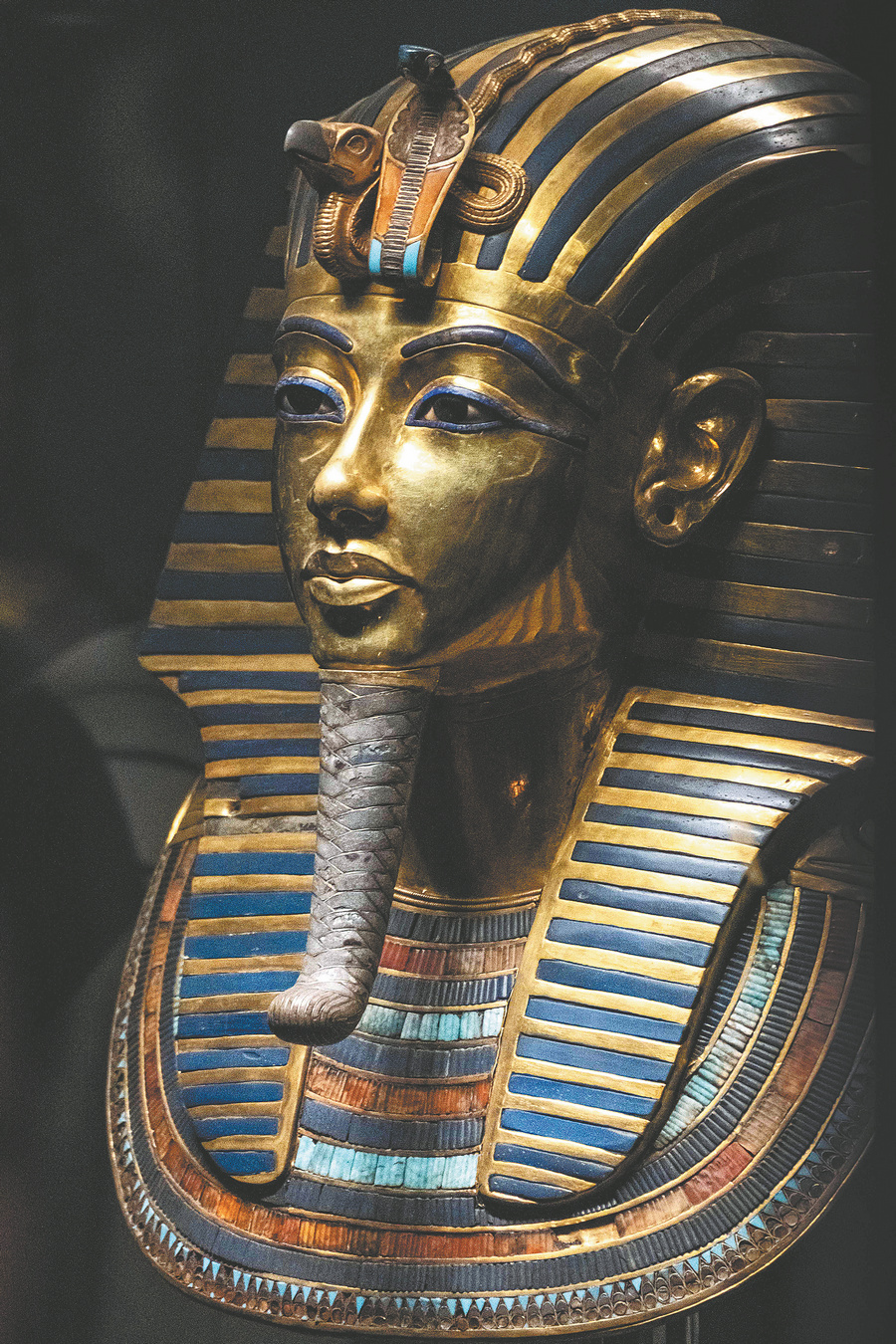

Imagine a snake — coiled, elusive, and steeped in meaning — emerging from the depth of the world's cultural history to leave its mark on human imagination. Perhaps it's the rearing cobra, poised on the golden mask of the Egyptian king Tutankhamun, a symbol of protection and divine authority. Or it might be the head of Medusa, the Gorgon whose hair of writhing snakes and petrifying gaze have haunted myth and art alike.

For the more artistically inclined, there's the celebrated Hellenistic sculpture Laocoon and His Sons, capturing the agonizing moment when the Trojan priest and his sons are ensnared by sea serpents. Then, of course, there's the serpent in the Garden of Eden, an enduring symbol of temptation and the central figure in the Christian tale of original sin.

In the Chinese zodiac, 2025 kicks off as the Year of the Snake on Jan 29. But looking at the bigger picture, snakes seem to slither just as prominently — if not more so — through the myths and symbols of other cultures, too. What stands out most about this enigmatic creature is its complexity — or, more precisely, its duality.

Ask the ancient Egyptians, and they'd tell you about Wadjet, the protective goddess of Lower Egypt and guardian of pharaohs, often depicted as a rearing cobra known as the uraeus. After the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt by King Narmer around 3100 BC, the cobra of Wadjet appeared alongside the vulture of Nekhbet, the goddess of Upper Egypt, on the pharaoh's crown, symbolizing the unity of the two lands.

Another equally prominent snake deity is Renenutet, the goddess of nourishment and harvest depicted as a woman with the head of a cobra who would watch over granaries. Central to Egyptian royal iconography, the snake — crawling close to the earth — was also celebrated for its connection to the soil, symbolizing fertility. The same attribute also linked the snake to the underground realm. Appearing in the tombs of pharaohs, they are expected to safeguard the king's journey to the afterlife.

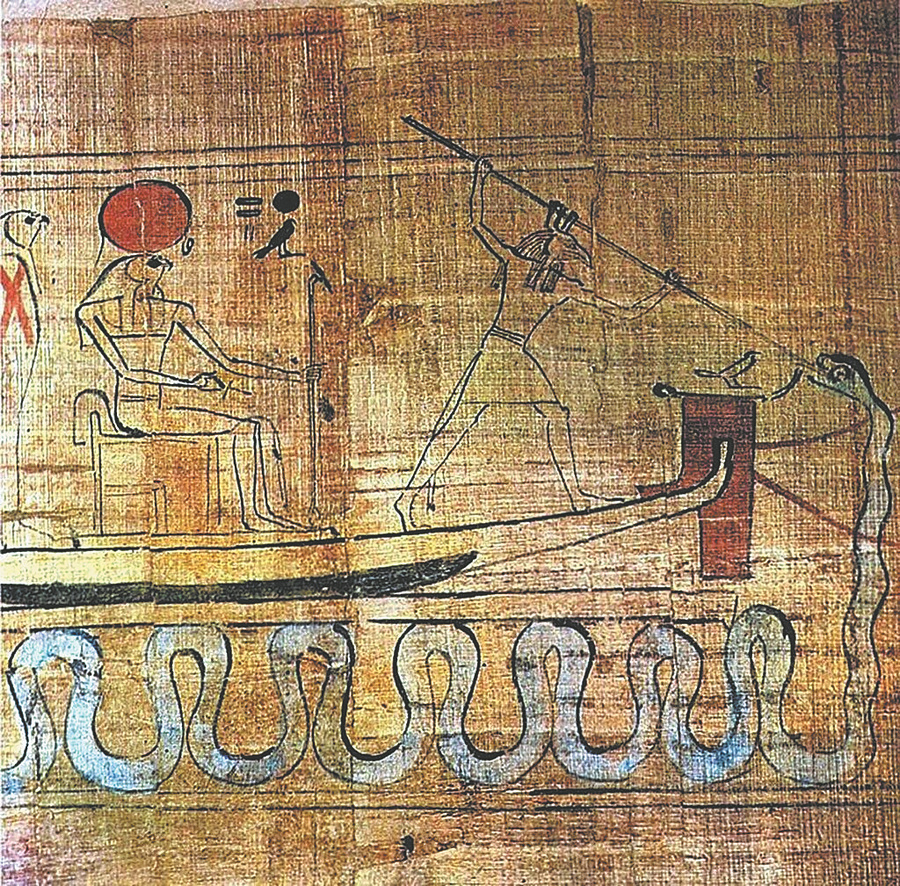

Yet, it is in the ancient Egyptian portrayal of the snake as a force of chaos and destruction that one can find some of the most profound philosophical wisdom of the civilization. Apep, a massive serpent, was the archenemy of the sun god Ra. Each night, Apep attempted to devour Ra's solar disk as it journeyed through the underworld. Though Apep was defeated every night, he could never be permanently destroyed. The nightly battle epitomized the Egyptian view of the perpetual struggle between order and chaos, and the constant need to maintain balance in the universe.

Snake bracelets from Egypt's Roman Period dating to the first century. THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART IN NEW YORK

In 332 BC, Alexander the Great conquered Egypt during his military campaign across the Persian Empire. After his death in 323 BC, his empire was divided, and Egypt eventually came under the rule of his general Ptolemy I, marking the start of the Ptolemaic Dynasty. The Ptolemaic rulers accepted and reinforced the Egyptian motifs including the snakes, bringing to Egypt snake-themed bracelets.

Cleopatra VII, the last active ruler of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt, was ultimately defeated by Octavian (63 BC-AD 14), who later became known as Augustus, the first Roman emperor. While Cleopatra famously killed herself by snakebite in 30 BC, Augustus, bringing Egypt under direct Roman control, aggressively embraced the symbolism of the serpent to bolster his sense of legitimacy. Coins minted during his reign often depicted a serpent coiled around an altar, signifying the emperor's connection to gods and divine protection.

It's believed that the snake in this context represented Asclepius, the Greco-Roman god of medicine and healing. Asclepius was often depicted holding a staff with a single serpent coiled around it, known as the Rod of Asclepius. In fact, sacred snakes were kept in temples dedicated to the god and sometimes allowed to roam freely around patients, as they were believed to be able to transmit healing energy.

Such was the powerful symbolism of the Rod of Asclepius that it was later adopted as the logo of the World Health Organization.

The gold burial mask of the ancient Egyptian king Tutankhamun on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. AMIR MAKAR/AFP

Some historians have suggested that the dual qualities of the snake — as both a symbol of healing and harm — stem from the nature of its venom, which can be both poisonous and curative. This paradoxical aspect aligns well with a ruler like Octavian, who was capable of delivering deadly strikes to his enemies and yet was eager to be perceived as a healer of the war-ravaged Roman world.

The Roman world embraced snake imagery, incorporating it into frescoes, mosaics, statues, and gold bracelets whose circular design evokes the ancient symbol of the Ouroboros — a serpent devouring its own tail. Derived from the Greek words oura (tail) and bora (eating), the Ouroboros is one of humanity's oldest symbols, embodying the cyclical nature of existence — seasonal changes, the rhythm of night and day, and the cycle of life and death.

Underlying these cycles is the concept of renewal, as reflected in the snake's periodic shedding of its own skin. In fact, in ancient Egypt, different types of snakes appeared in hieroglyphic writing and art, some carrying the meaning of rebirth and immortality.

Echoing the Egyptian theme of eternal life, the snake plays a significant role in The Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the oldest known works of literature, originating from ancient Mesopotamia around 2100 BC. In the story, Gilgamesh, the death-fearing protagonist, successfully retrieves the "Plant of Life" from the bottom of the sea, only to have it stolen and consumed by a serpent.

The loss, widely interpreted as symbolizing the inevitability of death, reinforces the epic's central theme: the wisdom gained through accepting life's limitations, and the importance of finding meaning within those limitations.

The massive serpent Apep attacking the sun god Ra, who's sitting on his boat with the solar disk atop his head. EGYPTIAN MUSEUM

A broken piece of clay bearing part of The Epic of Gilgamesh in cuneiform was on display at the Suzhou Museum in Suzhou, eastern China's Jiangsu province, during an exhibition from the British Museum last year.

Meanwhile, the story of Tutankhamun is being told through an ongoing exhibition at the Shanghai Museum titled On Top of the Pyramid: The Civilization of Ancient Egypt. The exhibition features a stone sculpture of the king, whose headdress includes a snake, largely damaged but still discernible.

It's worth noting that the Great Sphinx of Giza originally had a cobra on its forehead as part of its headdress, though it was almost entirely eroded over time. A guardian and a protector — that role of a snake was powerfully evoked by an ancient Egyptian hymn dedicated to Wadjet:

"May Wadjet, the Great Serpent, encircle you and protect you.