A bronze head with gold foil mask, unearthed from the archaeological site of Sanxingdui.[Photo provided by the Shanghai Museum and the Sanxingdui Museum]

In the public imagination of the Chinese, the words Sanxingdui (Three Star Mounds) are the equivalent of a myth: What they see in exhibitions focusing on this major Bronze Age civilization, including a current one at the newly opened Shanghai Museum East, doesn't seem to align very well with their previous experiences.

They shouldn't be blamed: Many of the items that have been unearthed at the archaeological site located in Guanghan city, Southwest China's Sichuan province, have pointed to a style and a tradition little known in the long canonized history of Chinese art and culture. These include a gold scepter measuring nearly 1.5 meters long, an upright bronze figure staring down from its more than 2-meter height, and, most surprisingly, a 135-centimeter-wide bronze mask with protruding pupils that can't help but make one wonder: "Who's behind it?"

"The pursuance of an answer to that question by Chinese archaeologists over the past four decades has led to a whole set of knowledge fundamental to our understanding of the formation of not only the Sanxingdui culture, but the entire Chinese civilization of which it had been an integral part," says Hu Jialin, curator of the Shanghai exhibition, who has sought, through more than 360 carefully chosen exhibits, to contextualize the story of Sanxingdui.

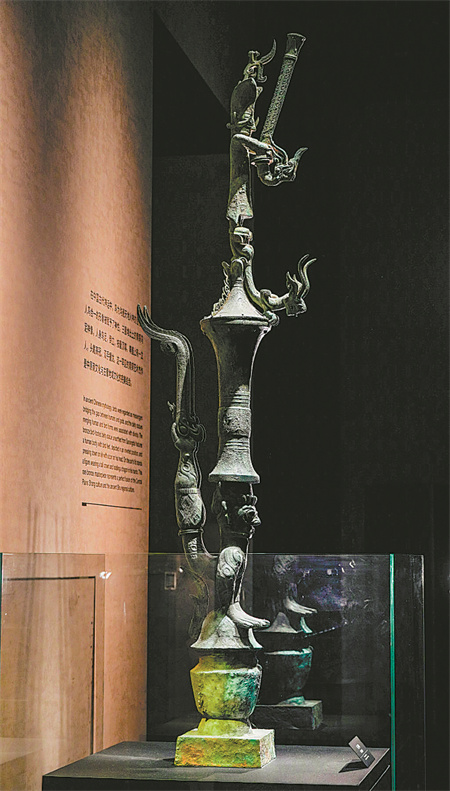

A hat-donning bronze figure with braided hair standing atop a giant mythical beast, unearthed from the archaeological site of Sanxingdui, Guanghan, Sichuan province.[Photo provided by the Shanghai Museum and the Sanxingdui Museum]

Two thirds of the exhibits have come from the archaeological sites of Sanxingdui and Jinsha. The latter is located about 40 kilometers south of the former in the Sichuan provincial capital of Chengdu and is considered to be its direct successor. These were put by Hu alongside other items excavated from sites on what he believes are "the ancient transmission routes", along which ideas, materials and people traveled as far back as around 3000 BC.

For those who had reached Sanxingdui from the plateau in the northwest (modernday Qinghai and Gansu provinces), there were mountains to climb and rivers to traverse. And for those from the east, the Yangtze River, running from west to east, acted as a ready conduit, connecting Sanxingdui to the various cultures that had flourished along the waterway. Among them was China's most prominent prehistoric jade culture, Liangzhu (3300-2300 BC). Rooted in divination and shamanism, the powerful belief system of Liangzhu is thought to have profoundly influenced Sanxingdui.

"Judging by what has been unearthed, the political entity behind the Sanxingdui civilization was a burgeoning state and a theocracy," says Hu.

That state was believed to be an ancient kingdom known as Shu. Shu historically refers to the area surrounding Chengdu city.

Details of a section of the central bronze figure, wearing tusk-shaped ear decorations.[Photo provided by the Shanghai Museum and the Sanxingdui Museum]

Sophisticated fusion

Sandwiched between a basin to the east and meandering mountain ranges to the west, the land, known today as the Chengdu Plain, was the work of several rivers and their tributaries that had run in a northwest-to-southeast direction. The same aquatic paths, intersecting with the Yangtze River at various points, enabled a constant cultural and demographic influx into the alluvial plain.

"For a large part of Chinese history, the land of Shu had been seen as a rather secluded place, sealed off in the mountains, where it spun its own legends and myths. Modern archaeology seemed to have initially confirmed that view, given the unusualness — some would say grotesqueness — exuded by artifacts from Sanxingdui, the bronzes in particular," says Hu.

"That was until one started to look at them really closely."

Among other things, Hu was thinking about the many bronze heads unearthed from Sanxingdui. Characterized by thick eyebrows, big eyes — both the brows and eyes were slanting upwardly toward the ears — wide noses and wider mouths, these sculptures emanate a sense of ferocity that is often wrongly associated with barbarianism, until people realize the sophistication of the art, and think otherwise.

"Their hair is typically done in two ways: braided or tied up at back with a hairpin. I am tempted to believe that the first group were positioned higher on the social hierarchy," says the curator, pointing to a bronze figure unearthed from the site and dated to around the 11th century BC. With its hair braided at the back, the man is standing atop a ritual vessel known as zun, which in turn is supported by what appears to be bird-man perched upon another, bulkier vessel known as lei, which serves as a pedestal for the entire design.

A grand bronze mask unearthed from Sanxingdui in 1986, noted for its protruding pupils.[Photo provided by the Shanghai Museum and the Sanxingdui Museum]

"Fusion — that is the key word for Sanxingdui," Hu says.

Wearing a fancifully adorned tall hat and elephant tusk-shaped ear decorations, the bronze figure is holding a dragon-form scepter which seems to echo another dragon winding down from the cover of the bronze zun under the man's feet. If the dragons, for all the creature's cultural connotations, stand as irrefutable proof to Sanxingdui's integration into the Chinese civilization, then the incorporation of the two bronze vessels into the design has shed tantalizing light into the process of that integration.

"Zun and lei, the two main types of bronze vessels found at Sanxingdui, were also among the most prevalent forms of ritual bronze for the lower reaches of the Yangtze River during that time," says Hu. "Researchers are still divided as to whether these bronzes had arrived at Sanxingdui by trade, or were brought there by immigrants via the waterway. But, one thing is for sure, they were embraced and prized so much so that they were, literally, melded with the local culture and religion."

According to the curator, although looking almost exactly the same as their counterparts that were discovered downstream, the bronze vessels from Sanxingdui sometimes feature drilled holes, which allowed them to be joined with locally made parts, bronze figures of men and animals for example.

In one case, a bronze zun was welded onto the head of a bronze man in a kneeling position, a process that had obliterated part of the pattern on the vessel's bottom.

"The same process had also subjected the culture of Sanxingdui to the far-reaching influence of China's Shang Dynasty (c. 16th century-11th century BC), whose time span coincided with that of what's known today as the Sanxingdui civilization," says Hu.

"Through unbridled imagination and sheer willfulness, the Sanxingdui people had added a spoonful of their own ingredients to the potent cultural mixture they had adopted and adapted," says the curator. "The latter was done with great panache, to fantastical effect."

A composite bronze ware from Sanxingdui made up of a scepter-holding bronze figure standing atop a ritual vessel known as zun, which in turn is supported by what appears to be a bird-man perched upon another bulkier vessel known as lei that serves as a pedestal to the entire design.[Photo provided by the Shanghai Museum and the Sanxingdui Museum]

Crypt clues

And when it comes to being fantastical, few things that have ever been unearthed from Sanxingdui could beat two grand bronze masks.

When the first one, measuring 138 cm in width and 65 cm in height, was lifted out of a pit back in 1986, its size and arched form had, for a few brief moments, allowed archaeologists to think that it was the backrest of a chair. In 2021, a similar-sized bronze mask was found in a nearby pit that has also yielded what's proved to be the left ear of the previous one, best noted for its remarkable pair of eyes.

Measuring at 3.5 cm in diameter, the round pupils of the eyes extended outward for nearly 17 cm to form two cylinders that look like gun barrels.

"In the land of Shu there once lived a ruler named Cancong who had protruding eyes and who made himself a king. Upon his death, he was laid to rest in a stone coffin, and those who came after him took up the practice," went the lines from a 4th-century book Huayang Guo Zhi (The Chronicles of Huayang), considered the oldest extant gazetteer, focusing partly on the land of Shu.

Hu notes that, in 1986, when archaeologists looked at the giant mask, they thought: "That's it!"

Thirteen years earlier in 1973, renowned Chinese archaeologists Tong Enzheng published his seminal study on the stone coffins built by people inhabiting the upper reaches of the Minjiang River, one of the major waterways that had functioned as a transportation route between the Chengdu Plain and the areas to its north and northwest.

"It is possible that this legendary figure named Cancong had led a major population inflow into the Chengdu Plain, where he founded the ancient kingdom of Shu," says Hu. "And this probably would have taken place around 2800 BC, the starting time attributed to Guiyuanqiao culture, the earliest Neolithic culture found on the Chengdu Plain, the site of which is a mere 16 km north of Sanxingdui."

"By the time the Sanxingdui civilization emerged, around 1600 BC, the kingdom had relocated multiple times, leaving behind traces across the Chengdu Plain," says Hu. "Sanxingdui was the capital when the kingdom was at its height."

Archaeological digs on the Sanxingdui site, measuring 12 square kilometers in total, have revealed a trapezoidal city, with four walls enclosing an area of 3.6 sq km, similar in scale to the inner city of the onetime Shang Dynasty capital in what is modern-day Zhengzhou, Central China's Henan province.

Forty meters wide at the base and 20 meters at the top, the remaining sections of Sanxingdui's city wall today serve as powerful reminders of the glory in which the kingdom was once bathed. In fact, the very name of the site and the culture — Sanxingdui, or Three Star Mounds — came from the remains of three, closely situated wall sections that had appeared to their discoverers as earth mounds.

A bronze head with hair tied up at the back with a hairpin, unearthed from the archaeological site of Sanxingdui.[Photo provided by the Shanghai Museum and the Sanxingdui Museum]

Towering curiosity

After Sanxingdui, there was only one stop to make — Jinsha, believed to be the political hub of the kingdom between 1100 BC to 600 BC. From there, the kingdom, of which few reliable references had been made by Chinese historical records, entered oblivion.

That was until the summer of 1986, when two local brick-factory workers accidentally stumbled upon what turned out to be a couple of dozen jade items. Further excavation by archaeologists led to the uncovering of two pits with openings measuring at about 14 square meters each. Together, the two yielded, among other things, hundreds of bronze, jade and gold artifacts. The discovery was even compared by some to that of the world-renowned Terracotta Warriors.

One dramatic moment, captured on black-and-white film, was when the grand bronze mask with protruding pupils was hoisted out of the earth. "What was it for? People have never stopped guessing since that moment," says Hu.

Pointing to its huge size, some believe that the mask itself was something to be worshiped, especially given its association with Cancong, the legendary ruler of the kingdom of Shu.

Five rectangular holes can be found on the mask — two on each side, and one right on the brow ridge. "It seems that these were for hanging or connecting the mask to something. And its overall outward curve has fueled speculation that this something could have been a totem pole or temple column, which the arched mask may have embraced," says Hu.

"If that is the case, the pole must be towering, and the temple, magnificent."