Corky Lee's picture of descendants of Chinese Transcontinental Railroad builders at Promontory Summit, Utah, on May 10, 2014. [Photo provided to China Daily]

As a youth Corky Lee saw a picture that not only violated history but, by omission, graphically conveyed the idea of ethnic outcasts. He would spend his life campaigning for racial inclusion and equality.

For Margaret Yee, May 10,2014 was a day much like all the May 10s of the previous decades and yet quite unlike any of them.

Again she was at Promontory Summit in Utah, where on May 10,1869, after seven years of construction, the eastward-extending railroad track built by the Central Pacific Company from Sacramento, California, met with the westward-extending one built by the Union Pacific from Omaha, Nebraska.

Standing on the elevated land and inhaling its cool, crisp air, Yee allowed her thoughts to run free and her spirit to reconnect with that of her ancestors. Two of her great grandfathers once toiled on the western section of the railroad.

"I was there every year, almost alone (as a Chinese American), until 2014," said the 72-year-old, who was joined that year by nearly 300 others-as well as a couple of dozen who had flown over from the southern coast of China, home to most Chinese immigrants to the US throughout the 19th century. All were there to lay claim to the glory to which their ancestors had undoubtedly been entitled but for 145 years had been denied them. There they stood-men and women, children and adults-under a cloudless sky and in front of two locomotives driven together for the occasion, looking more like antiques.

Facing them atop a red step ladder was a man in cap and jeans, right hand holding a camera, left hand slightly cupped beside his mouth as he called out to the crowd, with a bag slung across the front. The image was captured by a fellow photographer barely a minute before the man, known to his friends as Corky, pressed his index finger to complete what he called "an act of photographic justice".

For those in the know, that justice was missing on May 10, 1869, when what Yee calls the "champion picture" was taken of a big crowd in front of two locomotives at the summit to mark the completion of the railroad, the engineering feat hailed for "linking America from coast to coast".

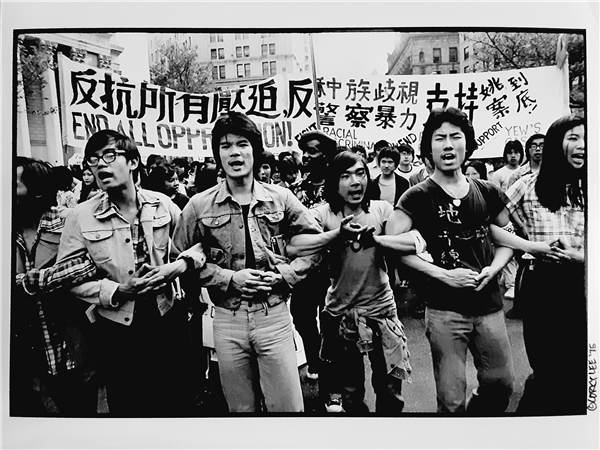

Under Lee's lens-a protest in Manhattan Chinatown against police brutality on May 19, 1975. [Photo provided to China Daily]

A protester being escorted away by police galvanized anger. [Photo provided to China Daily]

Yee's great grandfathers were not in the picture. In fact, not single soul of those 12,000 or more Chinese employed by the Central Pacific Company was. And yet it was they who had blasted and tunneled through the hard granite face of the Sierra Nevada mountains, and laid ten miles of tracks in one day-an unbeaten record for many years to come-once the snow blizzard relented and the terrain turned less forbidding.

"What Corky was trying to do was to set history straight. And he was able to bring all people together by simply hooking up with them and getting them excited," said Amy Chin, who was in the crowd. "He was relentless, at one time working with 16 organizations to make it happen. He was the Pied Piper whom we all followed in rediscovering and rewriting our own history in America."

On Jan 27 this year Corky Lee, Chin's friend for 40 years, died after suffering complications of COVID-19 in New York, where both had grown up in the backrooms of their own family laundries. He was 73.

Big news outlets such as CNN,NBC News, The New York Times and The Washington Post carried news of his passing-the kind of lavish attention he had fought to get for his fellow Asian Americans over decades, but that he felt he had never quite achieved.

At the same time warm tributes from his family as wells as journalists and activist friends flooded the internet and social media. One called his life "a ceaseless act of creative intervention in a history shaped by erasure", while others credited him for having built "the foundation of what it is to be an Asian American in this country", having "left us with what is likely to be the single largest repository of the photographic history of Asian Americans for the past half century".

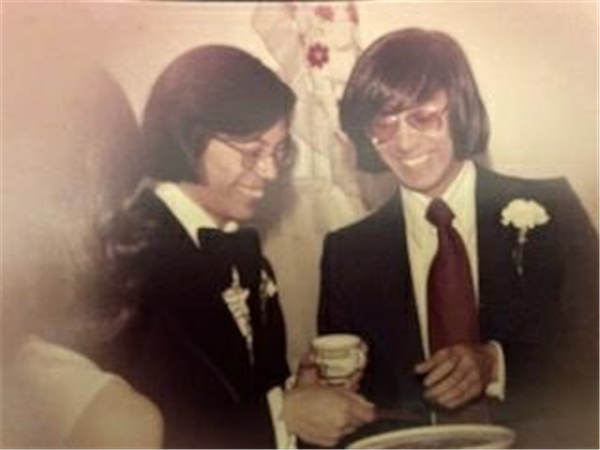

The number of pictures in that repository remains unknown, but it is thought to be in the tens of thousands. One of them, held close to heart by John Lee, Corky Lee's younger brother and his only surviving sibling, shows a sewing machine, one their mother hunched over whenever she had brought home unfinished work from the garment factory. Hanging on a nearby wall overlooking the sewing machine is a Chinese calendar and wedding photo taken of the Lee brothers' elder sister and her husband.

"While the gown and tuxedo the newly weds wore is symbolic of our adoption of and integration into American life, the sewing machine offers a metaphor for the struggle and hard labor upon which our life had been built and through which we contributed to America," John Lee said.

Behind it is a family odyssey. In 1925 Lee Yin Chuck, 17, arrived on the US west coast after a month at sea. From there he traveled by train to New York to join his cousins in the restaurant and laundry business. He would later return to China to marry before his wife gave birth to their only daughter, the one in the wedding photo, but it was not until 1946 when he was finally able to bring his wife and daughter to the US. The next year, Corky Lee, the eldest of the couple's four boys, was born.

Growing up, Corky, like herself, was stung by "the racism of not seeing ourselves", Chin said. "I cannot tell you how excited I was when, as a kid, I saw a Chinese person on television. I was pointing to the screen and shouting, 'Look! Look!'," the 58-year-old recalled, laughing. "It turned out that it was a commercial for laundry soap, and the person was playing a Chinese laundry owner.

Lee (left) with friends holding his pictures, including Karlin Chan (to Lee's left) a longtime activist in New York's Chinese community. [Photo provided to China Daily]

Corky Lee's rendition of his family history: his mother's sewing machine with his elder sister's wedding photo on the wall. [Photo provided to China Daily]

"So the struggle was not only to have our stories told, but to make sure how they were told. Corky understood that. He told an insider's story."

His pictures show a Chinese girl sporting a pageboy haircut standing beside her mother in a garment factory and a jaded-looking Chinese restaurant chef taking a rare break on the sidewalk-things that "people always know are there but have never bothered to take a look", to quote Karlin Chan, a longtime activist in New York's Chinese community.

Meanwhile, Lee was always after Chan and his fellow "bullhorn types" for images that cut against the stereotype of political apathy among Chinese Americans, long viewed as the model minorities-diligent and docile.

"I've always revolted against that concept," Lee once said. Showing up at every political rally and march in New York Chinatown, Lee captured on film raised placards, fluttering banners and interlocked arms of the protesters including Chan, who once played truant with several classmates to march in a protest in the '70s. "I was only reminded of it when I came face to face with Corky's picture of us at an exhibition," he said.

It was also the photographer's own youth, a youth spent searching for a new identity for himself and his generations from behind the camera, one that is distinctly different from that of his immigrant parents. "ABC from NYC" was what he called himself, ABC standing for American-born Chinese.

"Corky belonged to the first generation of Chinese Americans for whom college was no longer an impossible dream," Chin said. "The resulting mobility allowed them to be the bridge between Chinatown and the new world, and to demand for their own people what the rest of the society had access to, better housing and job opportunities for example."

One major event that Corky Lee took part in and documented involved protests in May 1974 when a construction company refused to hire Asian workers for a 764-unit apartment building planned for Chinatown in Manhattan, even as it ostentatiously called the building Confucius Plaza. The company later relented, agreeing to recruit minority workers including Asians.

However, it was what happened almost exactly one year later that "convinced me to do photojournalism", Lee said.

On May 19, 1975, almost every shop and factory in Chinatown was closed, with signs outside reading "Closed to protest police brutality". On April 26 that year a Chinese American engineer, Peter Yew, 27, watched as police brutally beat a 15-year-old for traffic violation in Manhattan Chinatown. After he intervened, he too was savagely beaten on the spot. He was later taken back to the police station, stripped, beaten again and arrested for resisting arrest and assaulting a police officer.

Lee, who was nearby, took pictures of Yew. He also photographed the ensuing protests. His image of a protester, face streaked with blood, being escorted away by police appeared on page one of the New York Post, galvanizing anger.

Two decades later, in March 1995, a 16-year-old Chinese American said to have been "brandishing a pellet gun", was shot dead by a New York police officer. Lee's poignant image taken outside what appears to be the police station shows at one corner a photo of the "shy boy" on a placard and at another the bulking, slightly out-of-focus figure of a policeman.

The magazine AsianWeek once quoted Lee as saying, "I'd like to think that every time I take my camera out of my bag, it's like drawing a sword to combat indifference, injustice and discrimination."

These pictures speak eloquently to what is happening in the US today, said Ryan Wong, an art writer and curator in New York.

"The Black Lives Matter movement makes us really examine our relationship to the police. Asian Americans have a history with police brutality, as do black Americans."

A Corky Lee picture of Chinese American beauties. [Photo provided to China Daily]

Lee's father knew better. The photographer once told Wong that his father said in the 1960s that "Martin Luther King is going to benefit all people of color". Lee's pictures from the '70s formed a crucial part of the 2014 exhibition Serve the People: the Asian American Movement in New York, curated by Wong to explore a nationwide phenomenon with New York at its center and Corky Lee its most avid documentarian.

"What the Asian American Movement did was try to name what the Civil Rights Movement in the '50s and '60s would be for Asian Americans,"Wong said. "A new Asian American identity was shaped by reclaimed histories, revolutionary politics, feminist awareness, third worldism and community organizing."

Speaking of the last one, in 1971, Lee with a couple of friends organized a street health fair in Manhattan Chinatown to provide free screening and preventative medicine to locals. The Charles B. Wang Community Health Center of today, which largely caters to underserved Asian Americans, grew out of that earlier effort.

"Since we were doing things for free, we got the label as being communist inspired," Lee said when he talked about his photography and activism in 2013.

"Some very conservative people felt that the 'Cultural Revolution' (1966-76) was moving from China to Chinatown, but of course there's no such thing."

His brother John Lee remembers the fractious time when there was "continued apprehension" mainly caused by tension surrounding the China-US relationship. The political atmosphere meant "many had to falsely align themselves" with the Nationalists in Taiwan, who "had US backing yet were defeated by the Communists during the civil war (the War of Liberation 1946-49)," he said.

"A turning-point", said John Lee, was United Nations' recognition of the People's Republic of China as the only legitimate representative of China to the world body, 50 years ago this October, thus ending Nationalist representation of the country. Both brothers took part in demonstrations supporting the PRC held near UN headquarters in New York. (As a photojournalist, Corky Lee covered both sides.)

A week later, the father, suspecting his sons were involved, said something "very, very remarkable", to quote the younger brother. "You know, there was a great deal of danger that the supporters of the (Chinese) mainland undertook, but what is right needs to be expressed-that's what our father said. And he just left it at that," said John Lee, who later went to law school and became a lawyer on the US West Coast.

The photographer visited the mainland twice, once in 1971, when he toured the family's ancestral home in Toishan (Taishan), Guangdong province, and in 2014, when some of his photos were exhibited in a museum in Beijing.

Asked about their mother's reaction to Corky Lee's continued activism, John Lee said,"She was petrified, and was always just worried."

What she may never have known was how highly her eldest son regarded her. "She couldn't read well, but she could feed well" was a line from the song Corky Lee played during his mother's funeral in 2012. It was written by his young friend Taiyo Na, a New York writer, musician and second-generation Japanese American.

Corky Lee "reimagined what racism told us we were through images of who we actually are," Na wrote after his death.

Under Lee's eye, babies not only appear in cradles right beside their garment factory-worker mothers, but were also seen as proudly worn forward-facing by their fathers demanding equal rights for themselves and their next generation.

A Corky Lee picture of Sikhs holding a memorial in Central Park, New York, a month before the first anniversary in 2002 of the Sept 11 terrorist attacks. [Photo provided to China Daily]

Lee (left) with his younger brother John in 1974. [Photo provided to China Daily]

The women who caught Lee's attention-then and later-were fighters, among whom Goldie Chu, a Chinese American who in 1977 stood before thousands in New York's Central Park to advocate for women's rights, and Dee Hamaguchi, a Japanese American and one of the first female boxers in the US.

Lee photographed other Asian groups-Japanese, Koreans, Indians, Philippines and Vietnamese among them-with equal enthusiasm as he did the Chinese.

"He's the adhesive, a bridge builder between different Asian communities that didn't always align with one another," said Chan, who believed the concept of Asian Americans virtually did not exist until the Asian American Movement of the '70s, and was inextricably linked to the Vietnam War. "And his pictures served to enhance that concept."

The response of Corky's generation to "the palpable anti-Asian racism of the era" was activism and solidarity, Na said.

"By banding together they had a bigger voice."

One of Lee's most recognized images was taken in Central Park one month before the first anniversary in 2002 of the September 11 attacks. It depicted a stoic-looking, lushly bearded Sikh wrapped in the US flag observing a memorial with his fellow Sikhs.

All except for a girl were wearing turbans, which had rendered them susceptible to hate crimes in the aftermath of the terrorist attack. The picture won Lee a journalism award. But the judge, in handing out the award, said that "there was a compelling, devious stare on the individual". "I disagree," said Lee."I'd like to find out who that judge was... It's an award that's marred."

In another of his post-9/11 pictures, a weary-looking American Chinese fireman was seen in his firefighting gear sitting on the front of his engine decked out with a flying dragon and the word Chinatown. Approaching retirement, he worked at the World Trade Center site right after the attack.

"Post 9/11, you never heard of a Chinese American fireman (from mainstream media)," said Lee, who said he wanted to show to the general public that Asian Americans are part and parcel of American society.

Lee and his longtime girlfriend Karen Zhou met around 2004. "I was very moved by the behind-the-scene stories he told of Manhattan Chinatown after 9/11 because I knew they were true," said Zhou."Chinatown is within walking distance of the World Trade Center. Post 9/11, it was a ghost town-the air quality was bad, people were worrying about another terrorist attack, the government wouldn't allow people to come in, the manufacturing of the garment factory stopped because they couldn't do delivery, even regular telephone services didn't go back for about six months."

Lee was there when the mainstream media were largely absent, "to make sure Chinatown was not forgotten", Zhou said. "He did the same when the SARS epidemic hit China and during the current pandemic."

Karen Zhou, Lee's girlfriend, bearing a picture of him at his funeral. [Photo provided to China Daily]

Lee with friends, many of whom he inspired, including Amy Chin (left), Zhao Wan (right) and Jennifer Takaki (second from right). [Photo provided to China Daily]

Together Lee and Zhou had many fond memories, including a road trip to New Orleans in 2010 on which the two interviewed and photographed Vietnamese shrimpers and fishers gravely affected by the oil spill following an explosion on the Deepwater Horizon oil drilling rig in the Gulf of Mexico that year.

"He shaped my life, while I was a big part of him as well," said Zhou, who has been described by Lee's closest friends as "always watching his back".

After seeing some of Lee's pictures, Zhou flew to Locke, in California's Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, to see a memorial toilet garden. It was built by Connie King, a Chinese American who saw toilets being thrown out by newcomers to her town, 50 kilometers south of Sacramento, the starting point for the western section of the 1869 Transcontinental Railroad.

"They told Connie that they were turfing out the toilets because they didn't want to sit on toilets that the Chinese had sat on," Zhou said. King salvaged the toilets and planted vegetables and flowers in them. The result is a memorial garden honoring those who not only built the railroad but also helped make California the biggest agricultural state. King died in 2009.

Like the mailboxes photographed by Lee, the toilets were once used by members of a bachelor Chinese immigrant society, formed as a result of the Chinese Exclusion Act. The law, barring all Chinese laborers from entering the state, was signed by president Chester Arthur on May 6, 1882-four days before the 13th anniversary of the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad.

"The act was only repealed in 1943, when China became an ally of the US in World War II," said Corky, whose father joined the Army Air Corps before serving under the command of General Claire Lee Chennault in the China Burma Indian Theater of the war.

"To ride with punches" was how Chan, Lee's longtime friend, describes the way with which the photographer sought to mitigate the emotional toll he inflicted upon himself doing what he was doing.

But certain things were always on his mind. In 1983, Vincent Chin, a Chinese American, was bludgeoned to death by Ronald Ebens, a Chrysler car plant supervisor and Michael Nitz, his stepson, a laid-off car worker. Blaming Japan's car industry for the unemployment of American workers, they killed Chin, thinking he was Japanese. Neither served prison terms.

In 2017, 34 years after Lee took pictures of the angry protesters demanding justice for Chin, he organized a candlelight vigil in front of the Ebens house in Henderson, Nevada. He wrote in a Facebook entry in June last year: "Chin would be 65 years old had he survived ... I will spend several moments remembering him, because it could have been me."

Lee was not killed by the most virulent racism, but rather, by "government neglect and institutional racism", Na said."The Trump administration's response to the pandemic was extremely poor, especially when it comes to marginalized communities," he said. "The vaccine was rolled out in mid-December and Corky, who was 73, never got the shot."

The photographer was back to filming in March last year wearing a mask, after a brief homestay in February.

Na remembers his conversation with Lee in 2001, not long after his wife Margaret Dea died of cancer."She would ask him, 'Why do you have to be the only one always out there taking photos?' and he would reply, 'Because I don't know anyone else who's doing it'," Na said. "Guilt was certainly something he carried with him at the time.

"The hard work also killed him. For many years he would go to photograph six or seven different events around town on a single day while working his day job at a printing company."

A Corky Lee picture of anti-racism protesters. [Photo provided to China Daily]

That day job had allowed Lee to squeeze Chinese characters onto ballots for the first time in New York's history. The city's board of elections had long refused to provide Chinese translations of candidates' names in voting machines in districts where many Chinese lived, citing a lack of space on the ballots and the printer's inability to produce Chinese characters.

In recognition of his work, David Dinkins, the first black mayor of New York City, proclaimed May 5,1988 to be "Corky Lee Day".

Na's last glimpse of Lee was during a zoom prayer held for him four days before he died. Gone was his "smile as wide as his lenses". The man, who might have been told-like many of his generation-by family seniors to keep the head down but somehow decided to "lead by being boisterous and out there", to quote him, was lying quietly on a bed in an intensive care unit "with his unshaven white stubbly hair, ventilator hanging on the jaw" Na said.

"Bruised Lee" the photographer used to call himself. It was a tribute to the Chinese American martial artist and silver-screen superhero Bruce Lee, while acknowledging the injuries he sustained fighting injustice.

"Corky had a grander vision for our place in the world, and it was to that rightful place that he intended to restore us," said Jennifer Takaki, a fourth-generation Japanese American who had been filming Lee since 2003 for her documentary Photographic Justice: The Corky Lee Story, scheduled for release before June.

"He was a walking encyclopedia," said Takaki, who, like others pulled into his orbit, found Lee to be "incredibly charming and intriguing".

"Nothing gave him greater pleasure than to discuss the story behind each one of his photos, something he did in my documentary."

Perhaps a tribute carried by Vulture, the culture and entertainment site of the magazine New York, best captures his effervescence. "Once he caught wind of your interests, he would rattle off a list of everyone you needed to speak to and offer to share their contacts, nonchalantly handing you a business card that designated him 'the Undisputed Unofficial Asian American Photographer Laureate'," the article said.

What he intended as dry humor is now seen by many as plain truth.

On Feb 6 the funeral procession wended through the shop-lined streets in Manhattan Chinatown before heading to Kensico Cemetery in the hamlet of Valhalla. Mask-wearing locals stood by the roadside waving goodbye and shouting "Thank you!" as blue garrison hat-wearing members of the Sons of the American Legion saluted the passing coffin. At one point Lee was a commander of the group, comprising offspring of those who served in the US Army.

"Corky is a patriot and a proud Chinese American," said Zhou, who was at the hospital to see Lee a couple of hours before he died and who was presented at his funeral with a folded Stars and Stripes by an American Indian veteran once stationed in Afghanistan.

Asked about the origin of Corky Lee's unconventional name, John Lee, who was in New York to bid farewell to his brother, explained that their father came to the US under the "paper (family) name Quoork", a practice that allowed one to enter the country by falsely stating that he or she was a blood relative of a Chinese American who had received US citizenship, after the Chinese Exclusion Act became law in 1882.

"'Corky' was bestowed on my brother by his schoolmates and teachers in junior high who pronounced our paper name as 'cork'," he said. It stuck even after the family readopted their original name Lee in the late 1950s. Young Kwok (in pinyin, Yang Guo), the photographer's given name, is "incredibly heroic" to quote his brother, meaning "build the nation".

It was also in junior high that Lee first came across that "champaign picture". After examining it closely, he failed to locate one single Chinese face."The seed may have been planted," said Lee in a short film titled Not on the Menu: Corky Lee's Life and Work.

Half a century later on May 10,2014 the man would start "a pilgrimage and a movement", as Takaki put it. Every May 10 since then, descendants of Chinese railroad workers from all over the US have traveled to Promontory Summit for a celebration and for the symbolic picture-taking by Lee, joined by a growing legion of his fellow photographers. In 2019, when the country celebrated the 150th anniversary of the railroad's completion, the group turned out in force.

"The Chinese, who were absent from the 1869 picture and absent once again on the 100th anniversary, had their presence and the spirit of their ancestors felt at the 150th, thanks to Corky," said Zhao Wan, who came to New York from China in 2008 to study theater arts at Purchase College.

Zhao, who calls Lee "my mentor", felt that spirit in 2014, as she danced barefoot on the rugged stones between the railroad tracks, in pure white with a conical straw hat tied at the back-the kind worn by those who laid the tracks. This was minutes before Lee clicked the shutter and a month before she unveiled off-Broadway her debut dance theater piece, Gen (Roots), which she directed, produced and starred in.

The play focuses on Chinese and Asian American women whose experiences intertwined with American history over the 150 years. The first chapter was dedicated to the wives of Chinese Transcontinental Railroad builders who had stayed behind, people whose long-lost story begs to be heard.

"I hit upon the idea somewhere during my discussion with Corky, whose pictures from the '70s and '80s provided both inspiration and stage backdrops to another chapter of my play," Zhao said. "Corky led us into the future by connecting us with the past. He's truly transgenerational."

Lee once said: "Fifty years from now, if people want to look at what the concerns of Chinese Americans and Asian Pacific Americans were, to see and understand, or try to understand, then my job is done.

"I can be happy six feet under pushing up daisies."